As I noted in the previous post, it is very difficult to find reliable information about Gerard Ceunis online, particularly in English. The most informative overview of his life and work that I’ve come across so far was written in 2007 by Christophe Verbruggen of Ghent University. Entitled ‘De kronkelige paden van Gerard Ceunis’ – ‘The winding paths of Gerard Ceunis’ – the article gives a vivid sense of the range of Ceunis’ artistic and literary ventures and associations, and includes some fascinating photographs, which I’ve reproduced in what follows.

The original article is in Dutch/Flemish, a language that I don’t speak, so I’ve had to rely on assistance from Google Translate for this English version. I hope my readers (and Professor Verbruggen) will forgive any mistakes or misunderstandings. The notes at the end are my own.

In 1964 Vooruit [1] was the only Flemish newspaper to pay attention to the fact: Gerard Ceunis had died in Hitchin, England. It was Johan Daisne [2] who wrote the piece in memory of ‘Uncle Gerard’, regretting that Flanders did not know its own history ‘and the men who helped make it what it is today’.

Johan Daisne (1930)

There are several reasons why Gerard Ceunis (1885-1964) fell between the folds of Flemish literary history. Undoubtedly the most important is that he fled his homeland in 1914 to make a fortune in textile sales in England. Out of sight, away from literary history. Other reasons are a lack of originality and not least his contrary nature. He refused to take on the shared habitus of his contemporaries and in doing so sidelined himself several times over.

At the beginning of the twentieth century the Ghent kuip (the old city centre) was the setting for a complex tangle of intrigues and friendships that often influenced artistic and literary positions. Gerard Ceunis was central to a number of these conflicts.

Until the age of thirteen Ceunis attended Sint-Lievenscollege in Ghent. He then went to work in the printing house where his father also worked. The family story would have it that the Ceunises lost a great deal of capital and social status in a very short time. He attended German courses at the Van Crombrugghe Society [3] and after working hours devoured the leading artistic and literary magazines in the library of Ghent University. His dream of becoming an artist is described in his diary of 1906, and it only grew stronger: ‘La vie de bohème is outrageously beautiful! An artist’s life – poverty – declarations of love in the attic – dancing at the fair – and in the end the girl dies. Chic! Is it strange that artists who can think so sensitively can sometimes be so dissolute, often leading a life that is not very exemplary.’

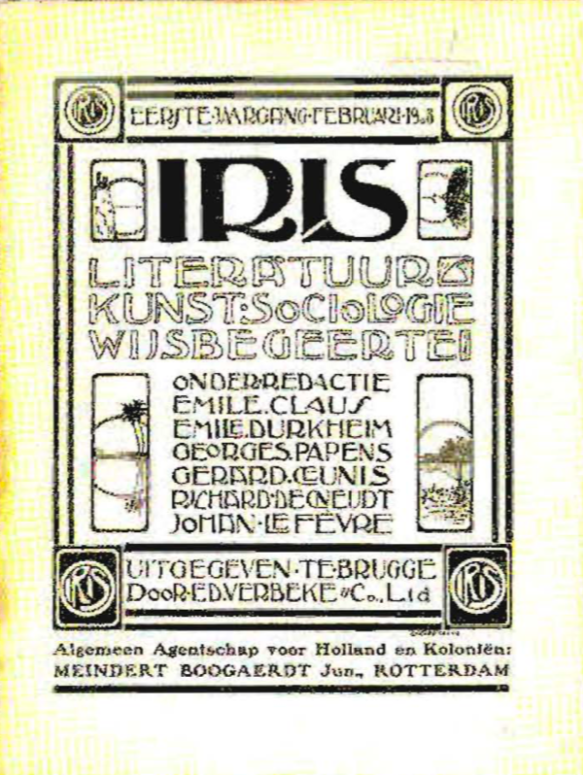

Cover of the magazine Iris (1908)

Together with Paul Kenis [4] and others, Ceunis wandered through the Ghent beguinages [5] and abandoned monasteries. He came into contact with students of the Ghent Academy who had moved in there and regularly sought refuge in absinthe. He thought he would like to become a visual artist, but first he would try to make a name for himself as a writer. After a short stay in Germany, he planned to set up a magazine on his own, the fastest way to launch yourself or a new literary programme in the literary field. When Vlaanderen, the successor to Van Nu en Straks, ceased to exist in 1907, Ceunis tried to use his magazine Iris to fill the gap. Nieuw Leven, by his fellow townsman and friend P.G. van Hecke [6], had a similar ambition. However, the carefully edited Iris quickly perished due to a lack of subscribers. Competition with other magazines was brutal and Iris‘ main editors had no financial means of their own to keep the magazine alive.

Paul Kenis (left) and Paul Gustave van Hecke

Ceunis joined the Reiner Leven [7] association in the hope of finding fellow spirits there. Reiner Leven exemplified the synergy between visual artists, writers, scientists and other intellectuals during the Belle Époque. P.G. van Hecke, Raymond Limbosh [8], George Sarton [9], Paul van Oye [10], Paul Kenis, all sought, among other things, through the activities of Reiner Leven, a way to demonstrate their social commitment and to give practical effect to their social criticism. Pretty soon Ceunis distanced himself from Reiner Leven and ‘De Flinken’ [‘The Courageous’], a group of feminists who had joined that society. He placed his fiancée Alice Vandamme in a difficult position, because she was a member of both clubs. Young women, in Ceunis’ opinion, should not be concerned with reading Maeterlinck [11] or with vegetarianism. He was dubbed an anti-feminist, a reputation he himself nurtured with his misogynistic public statements. It earned him the scorn of half of Ghent.

Like many other would-be intellectuals of the period, Ceunis flirted with anarchism. Bouncing back and forth between Max Stirner, [12] Nietzsche, but also Maeterlinck and Van de Woestijne [13], he developed an individualistic social vision that reflected his ideas about art.

In his essay Individualism, published in 1910, he summarised this as follows: ‘And if, when I say: love yourself, people, instead of proclaiming with hostility and envy, “see, that is the worst egoism, that is society’s rottenness”, would try to understand these words: We try not to love ourselves so deeply that we abhor all our weaknesses and flaws, all our wickedness and insincerity […] and so, good and true to the wonder around us, unconscious of its meaning, equal to the sun’s warmth and light, by this SUN = BEING.’

Many years later, Ceunis told Johan Daisne that this was the only thing he still looked back on with satisfaction. The essay also demonstrates that Ceunis was very talented. Not only does it read as an enlightening document of its time, it also shows a great ability to synthesise.

Unlike many of his contemporaries who embraced the aura of the committed intellectual, Ceunis never demonstrated a desire to commit to society. Nor was the cause of Flemish emancipation for him. Ceunis the individualist grew increasingly isolated. As far as is known. he was active only in the Literary Society, of which many writers were members at that time, hoping to legitimise their authorship. After the demise of Iris, he published two plays: The Captive Princess (1909) and Gothic Fairy Tale (1910). André de Ridder [14] from Antwerp was about the only one who believed in him and he also wrote the foreword to The Captive Princess. The reception of both plays was lukewarm; they were never staged. Not without justification was he accused of a degree of unoriginal imitation of Maurice Maeterlinck. The extent of Ceunis’ admiration for his fellow townsman is also evident from the name he gave to his daughter: Vanna, after the play Monna Vanna written by Maeterlinck in 1902. When André de Ridder took the initiative to set up the magazine De Boomgaard, Ceunis was first in line to act as its representative in Ghent. His former friends Van Hecke and Kenis were against the idea, and as a result de Ridder also dropped Gerard Ceunis.

Ceunis then decided to further develop one of his other talents. He enrolled at the Ghent Art Academy, from which he graduated in 1912. A year later he exhibited for the first time at the Ghent Salon. When he moved to England in 1914, his social network was limited. The numerous etchings in the attic room of his granddaughter’s manor house bear witness to a continuing friendship with the visual artist Jules de Bruycker [15]. In addition, he maintained contact with the parents of Johan Daisne, the ‘Flinke’ Augusta de Taeye [16] and [Leo] Michel Thierry [17].

Vanna Ceunis

When he was eighteen, to improve his English and his health, Johan Daisne spent the summer with Ceunis in Hitchin, Hertfordshire. He fell hopelessly in love with Vanna. She became one of the Six Dominoes for Women, a collection of stories from 1944. In the piece that Daisne wrote as an obituary of Ceunis in Vooruit, he looks back on his stay in England: ‘In my youth I walked there [the cemetery in Hitchin], dreaming among the graves. Sometimes I sat in the church tower staring endlessly at the summer opulence of the “commons”. A young and very blonde girl loved my company. Her name was Vanna.’

Once he had made his fortune, Ceunis left the management of his shops to his wife Alice and spent his days painting and philosophising. After the First World War, he evolved from an impressionism in the luminist style of Emile Claus [18] and Albert Baertsoen [19] in the direction of the more expressive style of Van Gogh. His work was highly thought of in England. Ceunis was discussed positively in the leading art magazines and national newspapers. A large-scale retrospective at the famous Arlington Gallery in London in 1930 was opened by the Belgian ambassador. The exhibition did not go unnoticed in Belgium either, but the recognition was short-lived. In 1933, despite Jules de Bruycker’s intercession, Ceunis’ paintings were even rejected at the Ghent Salon.

Gerard Ceunis, ‘Flemish Room’ (oil on canvas)

Before he passed away, Ceunis wanted at all costs to donate a painting to a museum in Flanders, so that he too could be ‘a little bit present’. He was unable to do this himself. ‘The “Flemish Room” must be given a place of honour,’ Daisne wrote in 1962, in one of his many letters to Ceunis, after which he once again referred to that ‘unforgettable time in Hitchin’ and his love for Vanna. For him, the painting was also a memory of that time. The AMVC Letterenhuis [20] accepted the gift after Daisne’s insistence. It is still part of the collection.

When Gerard Ceunis and Alice Vandamme fled to England in 1914, they also took with them their diaries and correspondence. In this way, a piece of Flemish heritage has ended up in the attic of an English country house that is currently inhabited by Vanna’s daughter. Between the etchings by Jules de Bruycker and dozens of paintings by Ceunis there are several boxes with items that deserve a place in the Letterenhuis, not so much from a literary-historical perspective, but from a cultural-historical perspective. Then Ceunis’ dream would come true: to be remembered in his native country.

Notes

- Vooruit: newspaper founded in Ghent in 1884 with links to the Belgian Workers’ Party.

2. Johan Daisne: pseudonym of Herman Thiery (1912 – 1978), Flemish author, pioneer of Dutch magic realism.

3. Van Crombrugghe Society (Genootschap): social-cultural society in Ghent, founded in 1857

4. Paul Kenis (1885 – 1934): Flemish writer and magazine editor

5. Beguinages: medieval houses for communities of lay religious women

6. Paul-Gustave van Hecke (1887 – 1967): Belgian author, journalist, art collector, patron and couturier

7. Reiner Leven (‘Purer Living’): student association founded in Ghent in 1905 by George Sarton (see note 9). See this article by Christophe Verbruggen.

8. Raymond Limbosch (1884 – 1953): Belgian poet and philosopher

9. George Sarton (1884 – 1956): Belgian-born American historian of science.

10. Paul van Oye (1886 – 1969): Belgian scientist

11. Maurice Maeterlink (1862 – 1949): Belgian playwright, poet and essayist

12. Max Stirner (1806 – 1856): German philosopher

13. Karel van de Woestijne (1878 – 1929: Flemish writer

14. André de Ridder (1888 – 1961): Belgian economist and literary critic

15. Jules de Bruycker (1870 – 1945): Belgian graphic artist, etcher, painter and draughtsman

16. Augusta de Taeye (1885 – 1976): Belgian nursery teacher and feminist. Wife of Leo- Michael Thierry and mother of Johan Daisne.

17.Leo-Michel Thierry (1877 – 1950): Flemish teacher and populariser of science. Husband of Augusta de Taeye and father of Johan Daisne.

18. Emile Claus (1849 – 1924): Belgian painter

19. Albert Baertsoen (1866 – 1922): Belgian painter and graphic artist

20. AMVC Letterenhuis: Belgian ‘House of Literature’ in Antwerp