In my last post I drew upon Johan Vanhecke’s biography of the Belgian novelist and poet Johan Daisne as a key resource to explore the intriguing connections between Daisne, Gerard Ceunis and the silent film actress Lillian Hall-Davis. The section of Johan’s book from which I quoted in that post occurs in the chapter entitled ‘Marquita’. The paragraphs immediately preceding the discussion of Lillian Hall-Davis provide a detailed account of the summer vacation that Daisne, whose real name was Herman Thiery, spent as a young man at the home of Gerard and Alice Ceunis in Hitchin, in 1929, and of the writer’s unrequited passion for the Ceunisses’ daughter Vanna. Although the account contains a good deal of information that is already familiar from Daisne’s own writings, and indeed occasionally quotes from those texts, it also contains a number of fresh and interesting insights. Vanhecke’s narrative begins on page 79 of the book (as before, all translations from the biography are my own):

With peace of mind he [i.e. Daisne] goes to England for the summer to spend the holiday in Villa Salve on Gosmore Road in Hitchin in Hertfordshire with Uncle Gerard and Aunt Lisa, the painter Gerard Ceunis and his wife Lieze Vandamme, one of the best friends of Augusta de Taeye from the time when they belonged to the group of friends known as the Flinken. Daisne tells the story of that summer at length in Aurora. Herman had got to know their daughter Vanna a year before on the beach at Knokke ‘and immediately found her very sympathetic and no less interesting. She also liked me from the beginning, I saw it, I don’t know how, in the softening of her sea-grey eyes.’

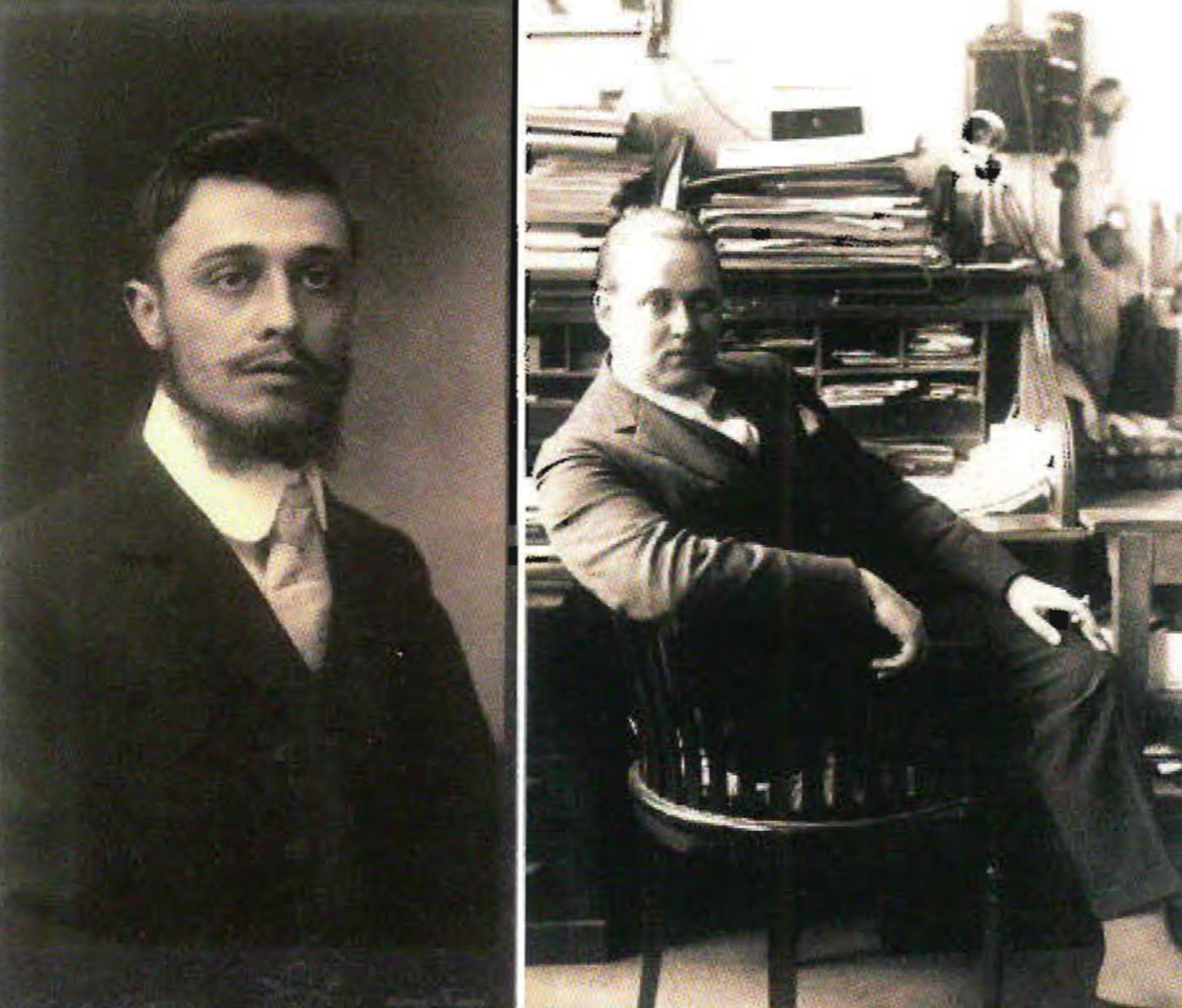

Johan Daisne (Herman Thiery) as a young man

Gerard Ceunis’ wife’s first name was actually Alice, but according to Daisne, she was known to friends and family as ‘Lisa’, ‘Lize’ or ‘Lieze’. Augusta de Taeye was Daisne’s mother: see earlier posts for further information about Augusta, Alice and the ‘Flinken’. The reference to Daisne and Vanna meeting for the first time on the beach at Knokke, presumably on a return visit to Belgium by the Ceunis family, confirms – and provides a specific location for – the story, related by Daisne in Aurora, which was eventually included in his Zes domino’s voor vrouwen of 1944. Knokke, on the Belgian coast near Zeebrugge, had been a favourite location for outings by the ‘Reiner Leven‘ and ‘Flinken’ groups, which included both Daisne’s parents and Gerard and Alice Ceunis, in their youth. In Aurora, Daisne provides further details of this initial encounter with the girl he there calls ‘Vavane’ [my translation]:

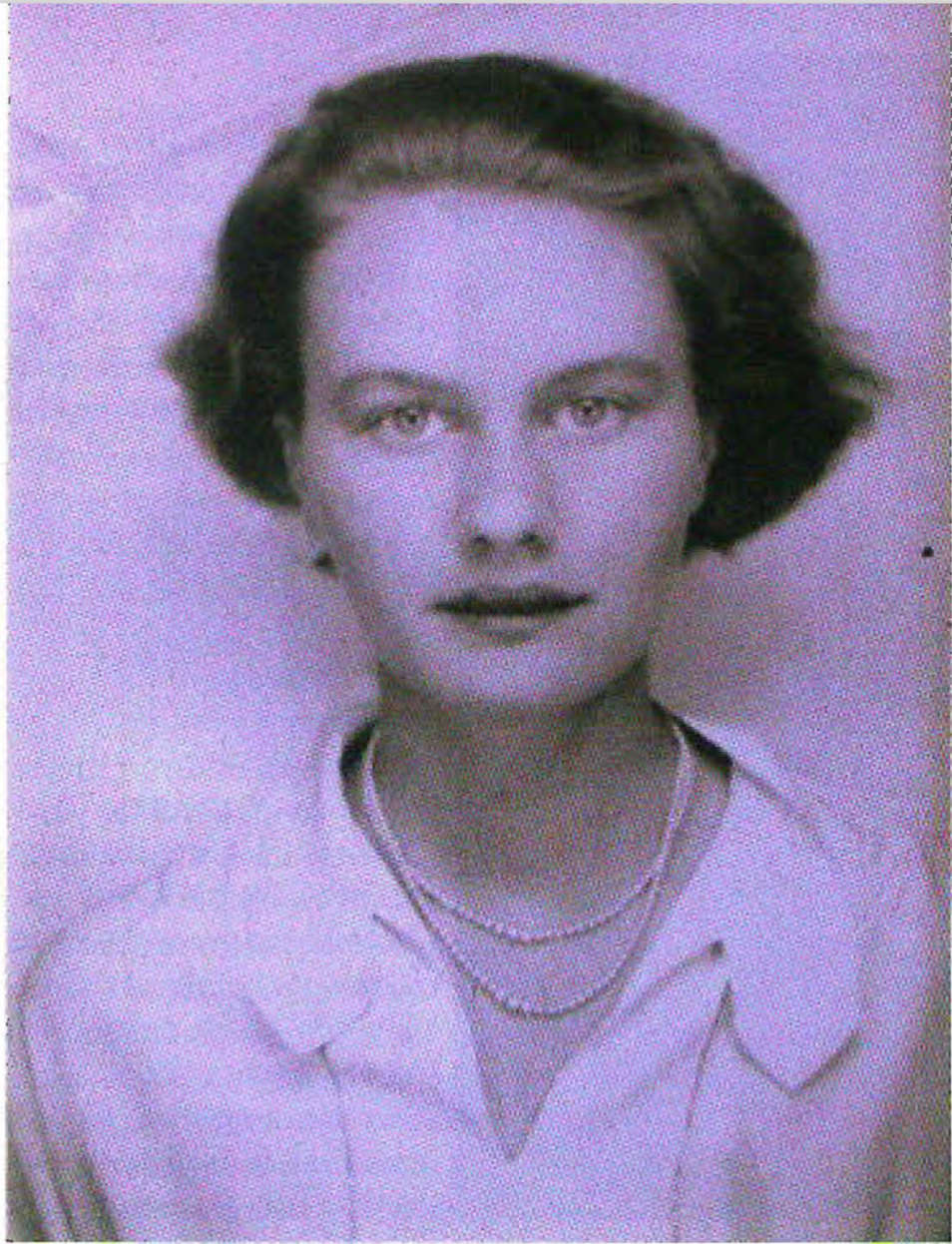

Vavane! I had met her by the sea, in a cloud of English cigarette smoke: a beautiful, tall girl, with a blonde pageboy haircut, a spoiled rich kid, wild and lazy, who wasted her time or frittered it away with horseback riding and dancing during the holidays, and during the year, at her ‘college’, with novels and chocolates. At first sight our characters appeared to be two extremes, but at the same time we resembled each other, because of I know not what warm sympathy.

Photograph of Vanna Ceunis, c.1938, in the Johan Daisne archive at the Letterenhuis, Antwerp

Venhecke’s biographical account continues:

Vanna was born in Ghent and named after a character from a play by Maeterlinck. Her father, Gerard Ceunis, had taken some steps in literature himself, with a play that was published in 1909 with a foreword by André de Ridder, The Captive Princess, and previously appeared in Vlaamsche Arbeid, and with The Simple Room. A Gothic Fairy Tale, which appeared in Flandria’s Novellesbibliotheek a year later. At the start of the First World War, he crossed over to England, since he was a member of the Civil Guard, and set up a second-hand fashion store with his wife. Now that it is running well, he has turned to painting.

As I’ve noted before, the young Gerard Ceunis was a great admirer of the plays of Maurice Maeterlinck and named his daughter after the eponymous heroine of Maeterlinck’s 1902 play ‘Monna Vanna’. One of the frequent criticisms of Ceunis’ own youthful dramatic output was that it was a pale imitation of Maeterlinck’s style. I quoted from one hostile contemporary review of The Captive Princess in this post. I’ve yet to see the text of Ceunis’ Gothic fairy tale, and this is the first time that I’ve seen its full title cited. For more information about Flandria’s Novellesbibliotheek, including Ceunis’ illustrations for its covers, see this post.

I’ve mentioned before that Ceunis’ membership of the Civil Guard appears to be one of the main reasons behind his decision to flee to England, after the German invasion of Belgium in 1914. Vanhecke’s account above contains the first suggestion that I’ve come across that Ceunis sold ‘secondhand’ [tweedehands] clothing in his stores: I think this may be a mistake.

Moreover, the suggestion in the next sentence that Ceunis ‘turned to painting’ following his success in business is perhaps slightly misleading. In fact, this ‘turn’ took place when he was still a young man living in Belgium. After his failure to break through as a poet and playwright, Gerard Ceunis began to study art at the Ghent Academy and exhibited in his home country before emigrating. It is, however, accurate to say that his later success in business gave him the leisure to devote himself, as Christophe Verbruggen puts it, to ‘painting and philosophising’.

Hitchin railway station, c. 1930 (via https://sunnyfield.co.uk)

The next section of Vanhecke’s narrative draws heavily on Daisne’s own accounts, both in Aurora and in his obituary for Gerard Ceunis:

The holiday starts badly, because in London Daisne misses his train connection to Hitchin. He sends a telegram in a combination of French and English, and fortunately finds Vanna on the platform hours later. It will be an adventurous and at times romantic holiday, with all kinds of tours, on foot and by car.

One evening they return so late from a movie (Desert Song, with John Boles) that they hardly dare ring the bell, for fear of Vanna’s mother’s reaction. Seeing a light in the bathroom, they throw pebbles against the window and are let in by Uncle Gerard in his pyjamas. Vanna loves the music of Ravel. In the afternoons they would listen to the Bolero and Daisne decides to translate the Pavane. ‘And on one of the last evenings, alone in the drawing room, we would read on the sofa, both of us wearing plaid. We took turns reading aloud, she English poets, I French, until we wearily let the book rest on our knees, secretly smoked a cigarette together, stared into the fire and finally lost ourselves blushing into each other’s eyes.’ Herman also introduces her to his beloved Les Miserables, which he has of course brought with him, and from Vanna receives Wuthering Heights, which he will not read until two years later.

Herman Thiery is in love and draws positive energy from this. Or as he puts it much later in Lago Maggiore: ‘The air of that summer was so filled with the scents of love that I thought I had found its object in Cousin Vanna’s blonde figure and grey look. And indeed, with the immediate image of that companion in mind, I then began my studies at the [university] with all the power of infatuation.’

But on the morning that he has to leave England, Vanna is sick in bed. He says goodbye to her, but does not dare to kiss her and is quite frustrated about it. Everything else he relates in the story Aurora about Vanna is strictly true (except that she doesn’t have a son but a daughter).

In fact, as well as getting the sex of Vanna’s child wrong, Daisne would (deliberately?) add another fictional detail in Aurora, describing ‘Vavane’s’ husband erroneously as ‘an English earl’.

The next section of the biography includes two stanzas from Daisne’s plaintive poem ‘Vanna’. My attempt at an English translation of the whole poem (which I draw on below) can be found in this post.

After her marriage in 1936 to a London lawyer, as a result of which he writes the poem ‘Salve’, there is no direct contact between Herman and Vanna, but Herman does maintain a correspondence with Aunt Lisa and Uncle Gerard.

When the latter dies in the 1960s, Vanna begins to write to him again, which inspires him to write the poem ‘Vanna’, of which he sends her a French translation in early 1974. He somewhat reproaches her for never expressing herself clearly but confesses that he has always loved her.

We were eighteen, long ago,

and you so tall and blonde and slim.

Sometimes you still write back with love

when I’ve sent you some nice thing.

.

But neither of us ever dared to say…

Shall I do it here and now?

Know this, by my eyes I swear:

I always loved you, to the end.

‘Salve’ today (via rightmove.co.uk)

I’ve yet to see a copy of Daisne’s poem ‘Salve’: in fact, this is the first reference to it that I’d come across, and I’d be very interested to read it. The next section includes an extract from an early version of Aurora which provides further insight into Daisne’s feelings of regret over his unfulfilled relationship with Vanna Ceunis:

However, he is very clear with himself in Chisinau, the first version of Aurora:

I did not respond, I was the little boy who did not dare, I was never clear, I who thought to lay all future hopes in barely veiled, brilliant words, which should be words of thanks, confessions, words of promise, and were only hopeless and bumbling obscurities. I alone have been dark, I alone am guilty, innocently guilty, because then I didn’t know any better and I couldn’t help it.

How clear were Vavane’s letters, how clear her dedication and her marginal notes in Stevenson’s ‘Virginibus et Puerisque’, my first and last Christmas present from her, after that English summer. How clear, above all, her last letter…

Vanhecke then offers an intriguing insight into Johan Daisne’s mixed feelings about the Ceunisses, and his resentment at having to rely on his friend Robert Mussche as an intermediary with them:

Herman may have had a problem with the general atmosphere at the Ceunis family home. He regularly talks about this with Robert Mussche, who stays in Hitchin in the summer of 1931: ‘I doubt whether you understand my feelings for them correctly […], they are also so difficult: in theory I love them, but in practice I can’t show it, because sometimes it moves me too much & furthermore, mainly, because I’m critical of their behaviour, cold condescension & capricious “grande geste”.’

In August 1933 he even had Robert Mussche provide her with the text of an article he had written about ‘Romanticism & Rationalism’: ‘The thoughts from it will probably best explain my attitude. Tell her above all about the distinction I make between our theoretical all-encompassing feelings of friendship and love & the practical attitude of criticism existing with it and alongside it.’

Robert keeps in regular contact with Vanna, but doesn’t like to talk about this with Herman.

On the weekend of March 10, 1934, this led to an almighty quarrel: ‘I have become accustomed to the fact that I always have to ask you if I want to know anything about the Ceunisses […] but the fact that you did not inform me on your own initiative of Vanna’s engagement, you must have understood that was anything but OK.’

Robert Muscche as a young man (via Johan Vanhecke’s biography of Daisne)

I’ve written elsewhere about Daisne’s friendship with the poet Robert Mussche (which is the main subject of the Basque novelist Kirmen Uribe’s docu-fiction Mussche) and about Mussche’s own visit to Hitchin, at his friend’s suggestion, and their rival affections for Vanna. I knew that the two friends temporarily fell out over this, and also as a result of Daisne’s apparently unflattering depiction of Mussche in Aurora. However, I hadn’t realised that Robert acted as a conduit for information about Vanna, nor was I aware of Daisne’s ambivalent feelings about his ‘uncle’ and ‘aunt’ in Hitchin. He writes about them elsewhere with such affection, that his use here of terms like ‘cold condescension’ comes as something of a shock.

Vanhecke adds a final detail about Daisne’s stay with the Ceunisses, drawing once again principally on the novelist’s own account in Aurora:

A small detail of the stay in Hitchin should not go unmentioned. One morning at the villa, Herman makes an important discovery. ‘There was no one down yet, the sun rose in the drawing-room and then by inspiration I followed the one ray that fell in that library, on a small item, it was called “La belle que voila” and standing up, strangely moved, I read that little, gripping story of unforgettable childhood love.

Liette, beautiful name!…I was still completely silent at breakfast, people asked what it was, and as I looked at Vavane’s sea-grey eyes, my heart became so soft that I was once again tempted into making a joke of it: I said I had a dream and told a variant of “La belle que voila.”’ Louis Hemon’s book is a real revelation. Herman immediately wants to translate it into Dutch, but after a few pages he gives up, because his Dutch seems too clumsy to him. Only thirty years later does he feel ready for a re-creation: The beauty of never again [De schone van nooit weer]… Whenever he rereads the story, he thinks back to England.

‘The beauty of never again…’ A phrase that nearly encapsulates Johan Daisne’s lifelong feelings of nostalgia and regret when recalling the magical summer he spent with Gerard, Alice, and above all Vanna Ceunis, in Hitchin.

Summer sunset over Priory Park, Hitchin: the view from near ‘Salve’