In 1929, when he was eighteen years old, the future poet and novelist Johan Daisne spent the summer with Gerard and Alice Ceunis in Hitchin, where he fell hopelessly in love with their daughter, Vanna, who would then have been about nineteen. Curiously, an almost identical experience befell another young Belgian writer, Robert Mussche, in the following year, the fictionalised account of which includes what must surely be the only reference to Hitchin in Basque literature.

Johan Daisne (Herman Thiery) as a young man

Born on 2nd September 1912 in Ghent, Johan Daisne, whose real name was Herman Thiery, was the eldest of the three sons of the influential teacher and populariser of science Leo Michel Thiery (1877 – 1950) and his wife, educationalist and feminist activist Augusta de Taeye. Both were members of the radical Reiner Leven (‘Purer Living’) society begun by the pioneering science historian George Sarton, which advocated pacifism, vegetarianism and feminism, while Augusta was also part of the Ghent feminist group ‘De Flinken’ (the Courageous Ones). It was through these networks that the Thierys befriended Gerard Ceunis and his future wife Alice Vandamme, and the two couples seem to have stayed in contact after the Ceunises moved to England in 1914.

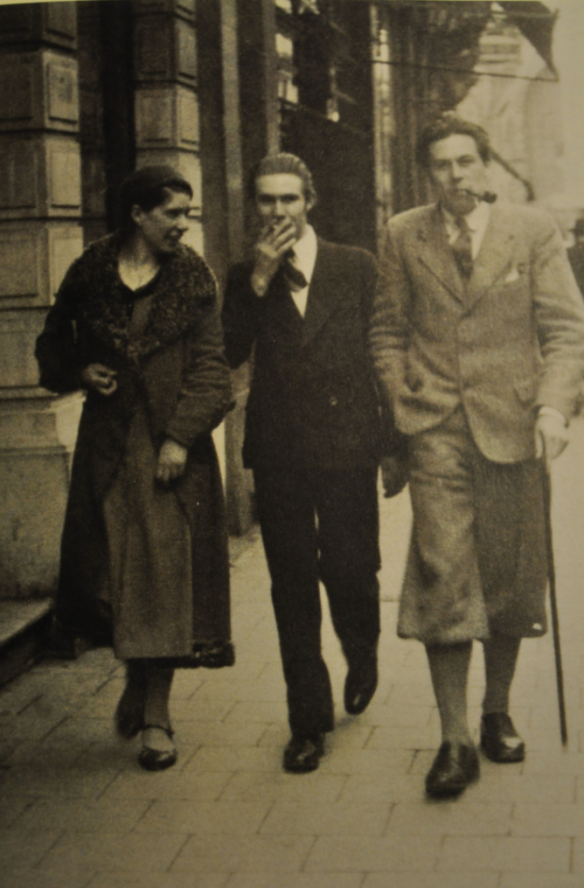

Augusta de Taeye, Leo Michel Thiery and one of their sons (possibly Herman), via http://www.ugentmemorie.be

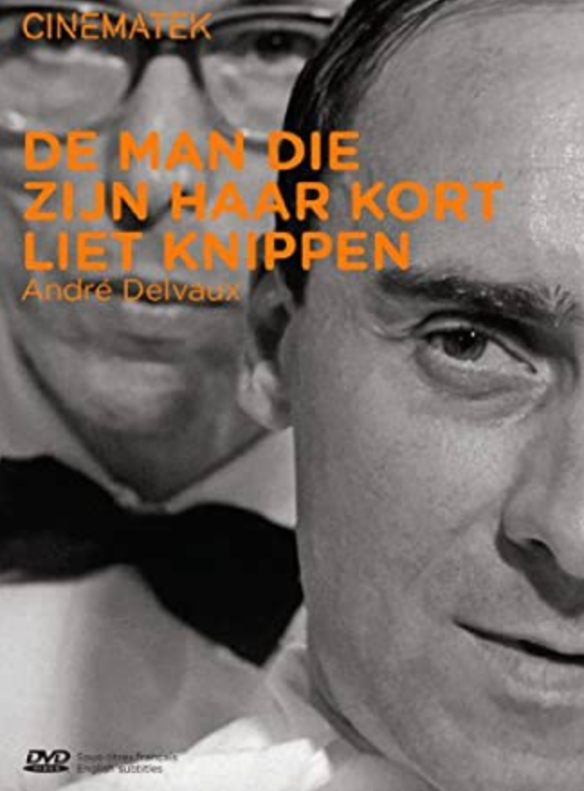

Herman Thiery attended the Koninklijk Atheneum in Ghent before studying Economics and Slavic languages at Ghent University, receiving his doctorate in 1936. He began writing under the pen-name Johan Daisne in 1935, with the publication of a collection of poetry entitled simply Verzen. This was followed by other poetical works including Het einde van een zomer (1940), Ikonakind (1946), Het kruid-aan-de-balk (1953) and De nacht komt gauw genoeg (1961). He was one of the pioneers of magic realism in Dutch, his best-known novels being De trap van steen en wolken (1942), De man die zijn haar kort liet knippen (1947) and De trein der traagheid (1953). He also wrote screenplays, radio plays and non-fiction. His 1947 novel was translated into English in 1965 as The Man Who Had His Hair Cut Short, and in 1966 it was adapted for the cinema by the Belgian director André Delvaux.

Apparently Daisne made a habit of pursuing hopeless and unrequited romantic relationships. In 1944 he dedicated one of the short stories in his collection Zes domino’s voor vrouwen (‘Six dominoes for women’) to Vanna Ceunis, even using her real name for the main character. A few extracts from the book can be found online. In them Daisne writes of the women who are the subjects of the stories, that ‘they were all “Marlenes”, with golden hair and waxy cheeks, endearing figures, haughty and tender at the same time, figures from a different world’. Besides Vanna, the other women in the stories were Marcheta, Claire, Aura, Brigitta and Greta. At one point, the author writes: ‘That was in Marcheta’s time, and in England I still loved Claire and Vanna. Wonders of the boy’s heart!’ (my translations)

Robert Mussche

Robert Mussche, Daisne’s rival for Vanna Ceunis’ affection, was born on 7th December 1912 in Wondelgem, a village close to Ghent. He was also a student at the Ghent Atheneum, where he met Johan Daisne; the pair became close friends. Coming from an impoverished background, Mussche had to quit his studies early to become the breadwinner for his family. Working by day in a bank, by night he taught himself English and Spanish and read the works of Zola, de Musset, Lamartine and others, at the same time being swayed by the ideas of Karl Marx.

At the age of seventeen Mussche began to write poetry, strongly influenced by the authors he had been studying. In 1936 he published the collection Oasis under the pseudonym Rudo Reyniers, and in the same year his poems were included in a collection of work by fourteen young Belgian poets.

Mussche’s youthful idealism prompted him to travel to Spain during the Civil War, sent there as a reporter by the newspaper Vooruit. While there he adopted Carmen, an eight-year-old Basque girl orphaned in the bombing of Guernica, bringing her back to his home in Ghent, though after the war she returned to Spain. In 2013 the story of Mussche’s life, and especially his time in Spain and his adoption of Carmen, was the subject of Basque novelist Kirmen Uribe’s much-praised ‘docu-fiction’ Mussche, translated into Spanish as Lo que mueve el mundo (‘What moves the world’). I came across references to the book while carrying out a Google search for information about Vanna Ceunis, which led me to a digital copy of the original Basque text. It was something of a shock to find references to Hitchin, and indeed Gosmore Road, in a strange language which at first I failed to recognise.

The cover of Kirmen Uribe’s ‘docu-fiction’ Mussche (2013)

Kirmen Uribe (via https://commons.wikimedia.org/)

My knowledge of Basque (Euskara) is even more minimal than my understanding of Dutch, which means an even heavier reliance on Google Translate, so I apologise in advance for any inaccuracies in the very loose translation of the extract that follows, in which Johan Daisne is referred to by his real name, Herman:

Herman would travel to England in the summer, spending three or four weeks at the Ceunises’ house. The Ceunis family were originally from Ghent, but some years before they had moved to Hitchin. Gerard Ceunis had been a friend of Michel Thiery in his youth, and they were eager to welcome Herman into their home, at his father’s request, so that he could learn English. During that summer of 1929, Herman could hardly stop talking about his friend Robert, or about the things they had done together, suggesting that he too would like to learn English in Hitchin. The fact is that the boy talked so much about Robert to those in the house, that in the following year, in the summer of 1930, Robert was also invited to Hitchin. He spent fifteen days there in a stylish house called ‘Salve’ on Gosmore Road.

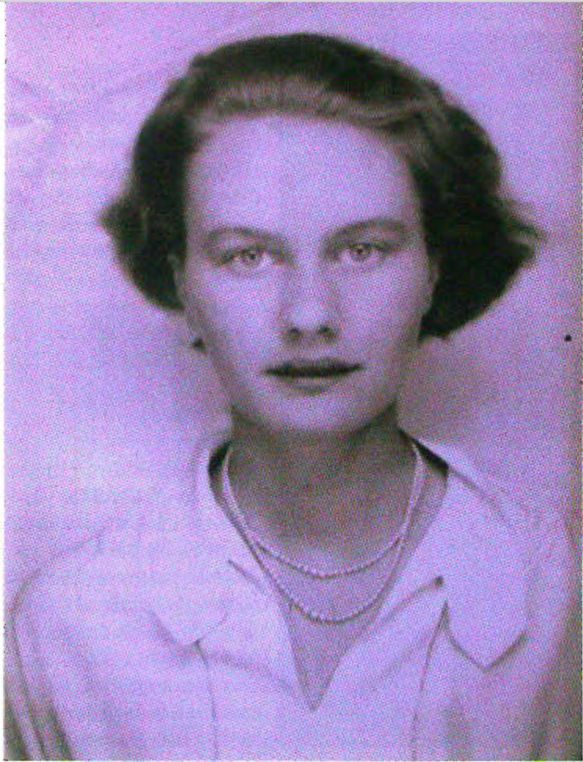

Vanna was the daughter of the house. She was about Robert’s age. Judging by the photo that she gave to Robert, Vanna was a beautiful girl. She has pale eyes, well drawn lips. Short hair. She was on the verge of becoming an elegant young woman. She is wearing a white shirt and a pearl necklace. A fine woman. A keen, penetrating glance. A girl to fall in love with.[1]

Photograph of Vanna Ceunis

(via Christophe Verbruggen, De kronkelige paden van Gerard Ceunis , 2007)

That’s what happened to Robert. And so he told Herman, on a postcard written on the voyage back from England, that his life had changed, that he was unable to erase the image of Vanna: ‘By the window, her hand laid on the glass, that fine hand. And the rays of the sun in her blue eyes.’ Robert gazed at her, but dared go no further.

Vanna was not as romantic as Robert. They liked each other, especially their conversations about literature. She was a widely read girl and was planning to study literature at college. On the other hand, that wasn’t everything for Vanna: she had other interests.

One morning, while Robert is asleep in his room, Vanna whistles from the street. Robert goes to the window and sees Vanna sitting outside on a motorcycle.

– Are you coming?

Robert has never ridden a motorcycle. He hesitates at first, out of shame, but then says yes.

– Hold me around the waist!

He reaches out for Vanna’s narrow waist and she takes them along the winding lanes of England. The wind blows through the girl’s shirt. Robert can feel her waist in his hand. He hesitates, as if he wasn’t already suffering enough. Vanna, on the other hand, is in control, she takes the bends with certainty, laying her body down and moving the machine to one side and then the other. Her skill impresses Robert and he admires her for it.

Herman’s response to Robert’s letter was: ‘Don’t think so, Vanna is mine.’ Herman had also fallen in love with the girl the year before and he wanted her as well.

Vanna, however, was not anyone’s. She didn’t give her assent to either of them. She married an English boy. And from a letter sent to Robert in 1940, we know that in the Second World War her husband served in the British army, on the front lines.

Nothing is known about Vanna after that.

At the end of the fifteen days, Vanna gave Robert a book. Written by Matthew Arnold, with the title ‘Essays in Criticism’, Macmillan and Co., New York, it carries the dedication: ‘Just an old book I am very fond of and thought you might enjoy reading. Very Best Wishes. Vanna’. And the following words are underlined: ‘More and more, humanity will realise that we need to turn our attention to poetry in order to interpret, reassure, and make sense of life. Science is without poetry.’

Robert was thinking about those lines from Vanna as he took the return boat, staring at the waves. What did Vanna mean by that? Was she really talking about poetry or was she saying that his character was too cold?

Robert couldn’t make up his mind whether to stay in Hitchin. The boy was so confused about Vanna that he seemed to have a longing to return to England, as if he had never completely left. At least that’s what Herman wrote at the time.

Their rivalry for the affections of Vanna Ceunis led to a temporary rift between Robert Mussche and Herman Thiery/Johan Daisne. A second falling out would occur when Daisne modelled a character in his novel Aurora on Mussche. The latter was unable to come to terms with the pathetic and sickly character in the book and was deeply hurt. However, the breach was eventually healed when Daisne (quoting Goethe) persuaded Mussche that there was a difference between ‘Wahrheit und Dichtung’ – truth and poetry.

Robert Mussche, Johan Daisne and an unnamed friend (unverified)

Robert Mussche eventually married Maria Op de Beeck and when their daughter was born in 1942, she was named Carmen, after the Basque girl the writer had rescued. During the Second World War and the German occupation of Belgium, both Mussche and Daisne joined the resistance, with Mussche playing a particularly active role as part of a communist faction, under the pseudonym ‘Julien’. In 1944 Mussche was arrested by the German authorities and taken as a political prisoner to the Neugamme concentration camp. In April 1945, the entire population of the camp was transferred to Lübeck by ship under SS surveillance. Deceived by the sight of German uniforms, Allied planes bombed the ship, killing most of those on board, including Robert Mussche.

A year after the war ended, when there was no longer any hope that Mussche would return, Johan Daisne published a touching tribute to him: In memoriam Robert Mussche, (Rudo Reyniers, Julien), 1912-1945, which included a number of his late friend’s poems.

In 1945 Johan Daisne/Herman Thiery was appointed chief librarian of the city of Ghent. He would always remember his ‘unforgettable summer’ with the Ceunis family in Hitchin, and his love for Vanna. In his 1964 newspaper obituary of Gerard Ceunis, Daisne wrote: ‘In my youth I walked there [the cemetery in Hitchin], dreaming among the graves. Sometimes I sat in the church tower staring endlessly at the summer opulence of the “commons”. A young and very blonde girl loved my company. Her name was Vanna.’ Johan Daisne died in Ghent on 9th August 1978 at the age of 65.

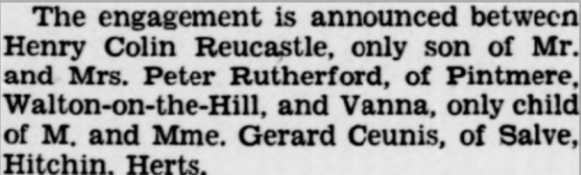

Notice in the Surrey Mirror, 6th July 1934

As for Vanna Ceunis, more is known about her life than Uribe’s novel implies. From online records of Bedales, the co-educational boarding school in Steep, Hampshire, I’ve discovered that Vanna was a pupil there in the late 1920s. And a report in the Hampshire Telegraph from 6th July 1928 lists her among the Steep Shakespeare Players who ‘delighted large audiences’ with their performances of Much Ado About Nothing. Exactly eight years later, on 6th July 1934, the Surrey Mirror announced the engagement of Henry Colin Reucastle Rutherford, only son of Mr and Mrs Peter Rutherford of Pintmere, Walton-on-the-Hill, and ‘Vanna, only child of M. and Mme. Gerard Ceunis of Salve, Hitchin, Herts’. The couple were married in Chelsea in 1936 and their daughter Teresa was born in Surrey in 1939. It seems that, after her marriage, Vanna often went by the name Jeanne, which I believe was her middle name. Under this name she and Teresa can be found, towards the end of 1939, living with her Rutherford in-laws in Surrey, presumably while husband Henry was serving in the army.

Henry Rutherford died in Surrey in 1980, and Vanna Jeanne Rutherford, née Ceunis, died in Hertfordshire in 1997. She was 86 years old.

Note