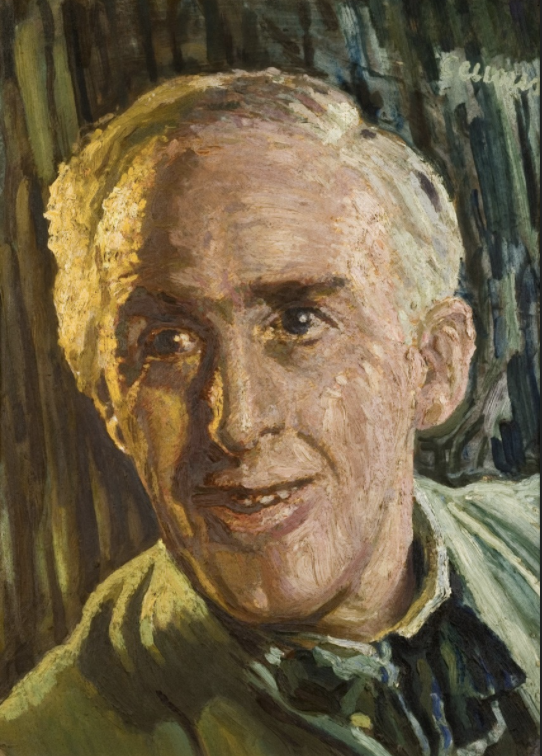

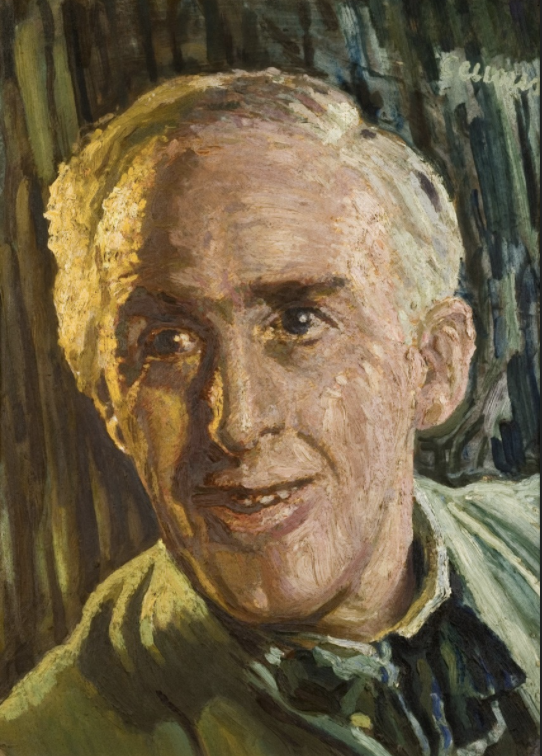

Gerard Ceunis, ‘Reginald Hine’ (© North Hertfordshire Museum)

Can you picture him, tall, thin Hine? The strongly moulded head, thrust forward on a slightly bent frame, the bronzed face, the ironic curved mouth ready to unfold into a cheerful and engaging smile, the keen blue eyes and the grey longish hair flowing in the wind?

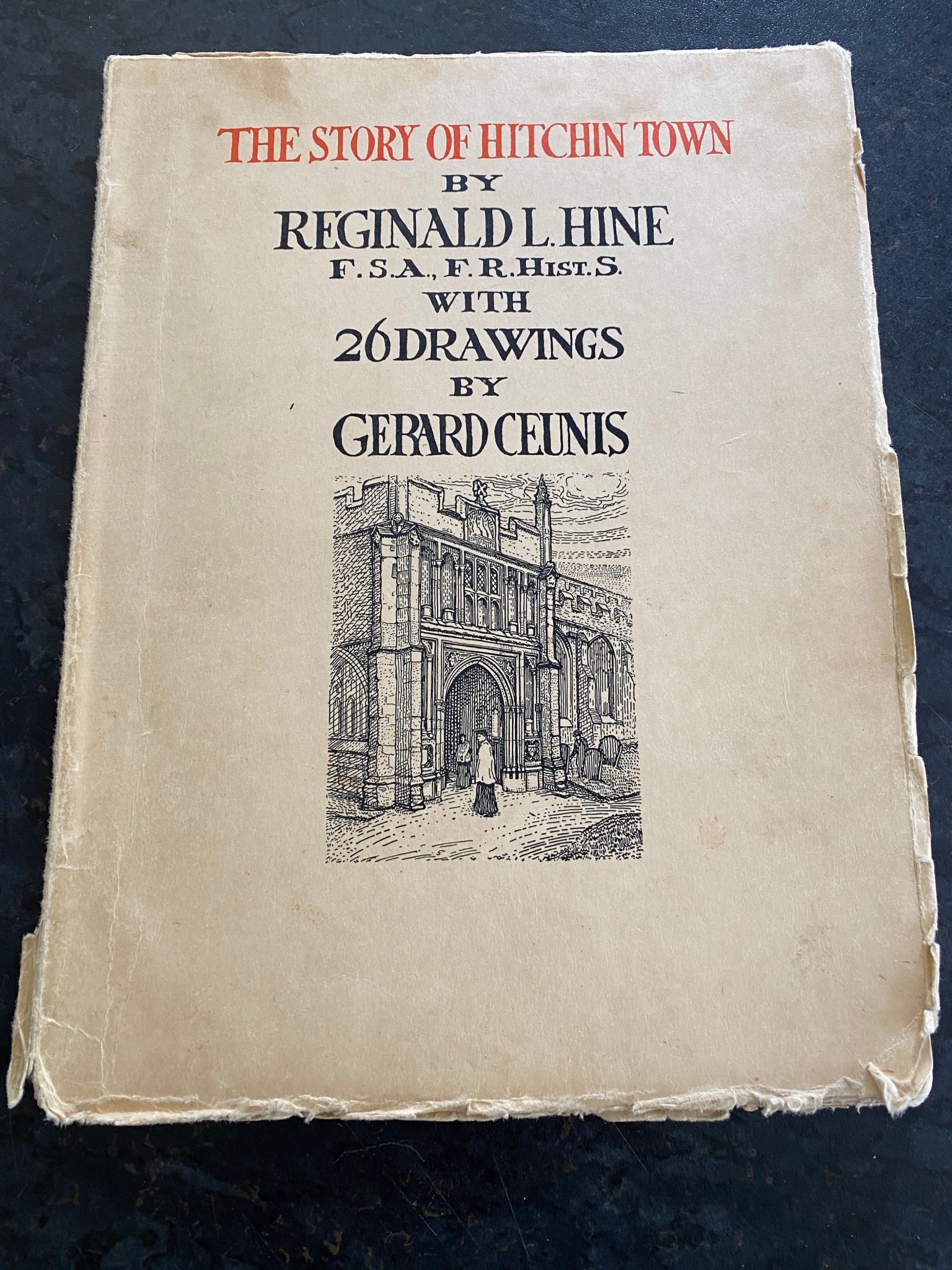

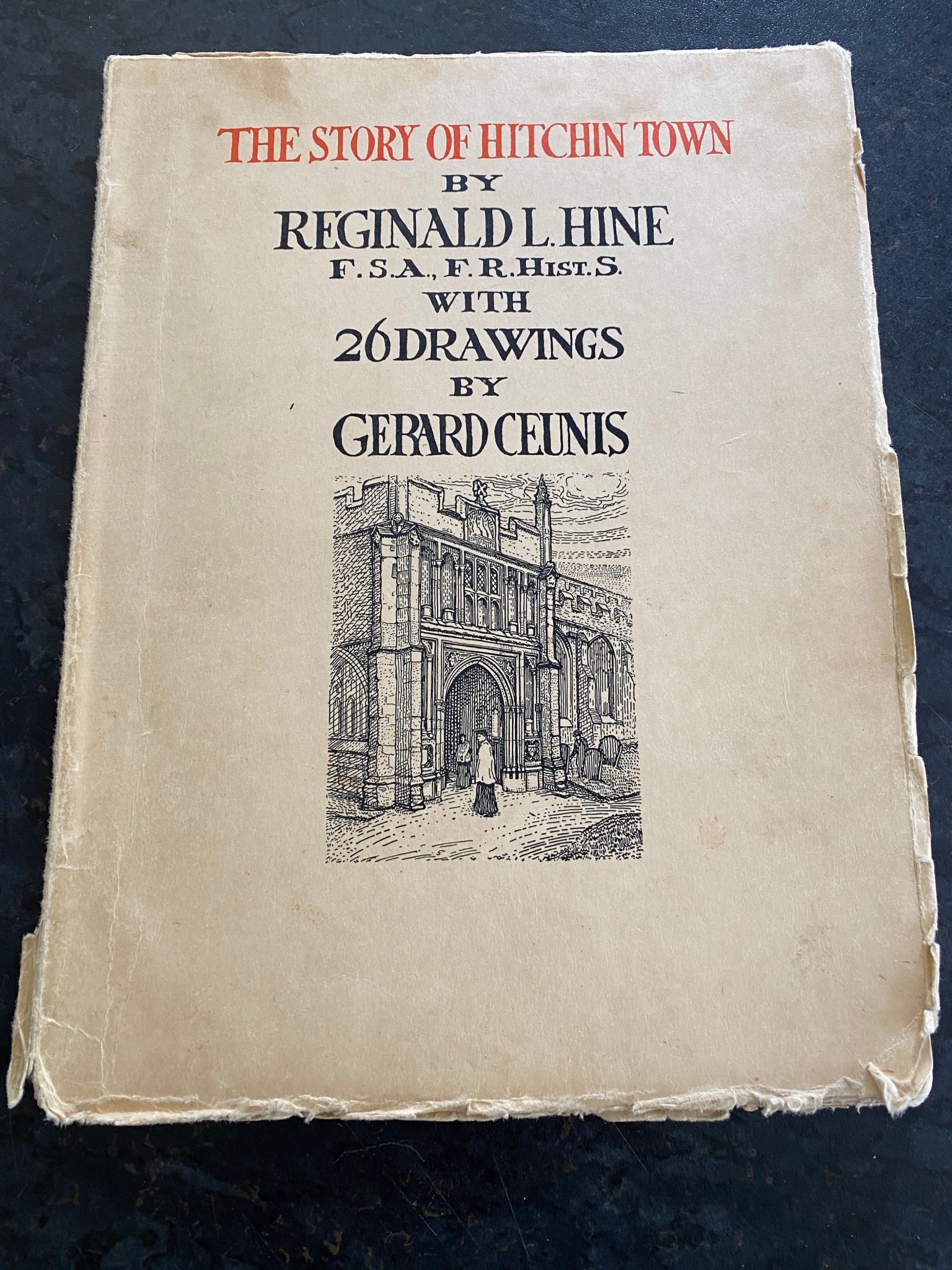

These words were written by Gerard Ceunis (and quoted by Philip Wray here) about the Hitchin historian Reginald Hine, with whom he collaborated on The Story of Hitchin Town, producing 26 drawings to accompany Hine’s text. Frustratingly, the publication bears no date, but it seems to have been produced in the years immediately preceding the Second World War.

Reginald Hine (1883 – 1949), whose portrait by Ceunis is reproduced at the top of this post, was a solicitor whose real passion was local history. His publications included a two-volume History of Hitchin (1927 and 1929), Hitchin Worthies (1932) and Confessions of an Uncommon Attorney (1945), as well as shorter books such as The Story of the Sun Hotel (1937) and A Short History of St Mary’s Church, Hitchin (1930).

The pioneer of English local history W G Hoskins described The History of Hitchin as ‘first class’, while G M Trevelyan claimed that he had ‘nothing but admiration for the method, plan and style of it’. More recently, however, doubt has been cast on Hine’s research methods and use of sources, with Hitchin Historical Society highlighting ‘his willingness to employ a mode of presentation more akin to storytelling than to academic caution’.

The Story of Hitchin Town is certainly better thought of as a series of connected historical anecdotes, rather than as a detailed academic history. In the first chapter, its author describes the book as ‘not an official, not even an un-official guide’, and refers ‘serious home students’ to his other writings, listed at the back of the book.

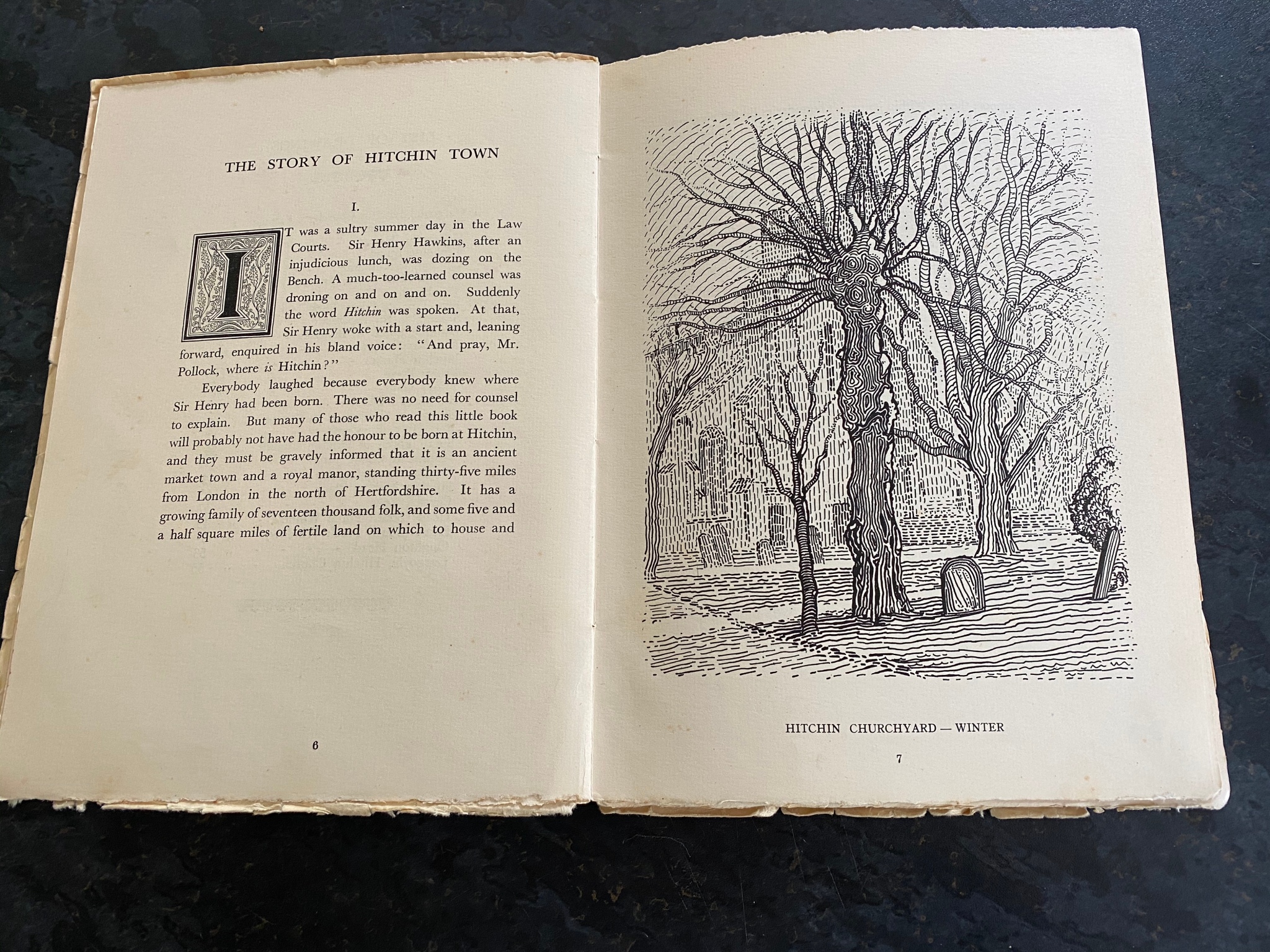

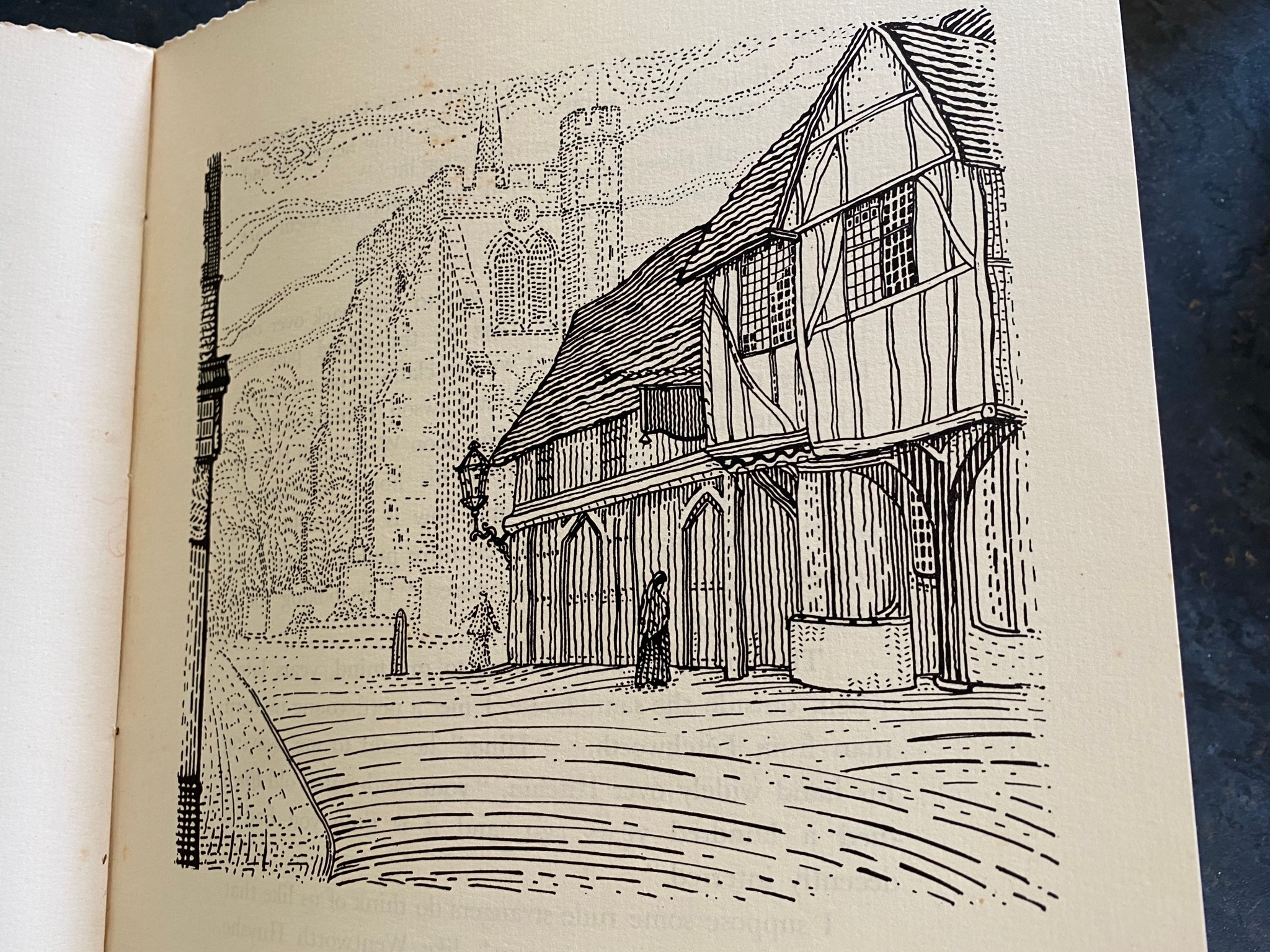

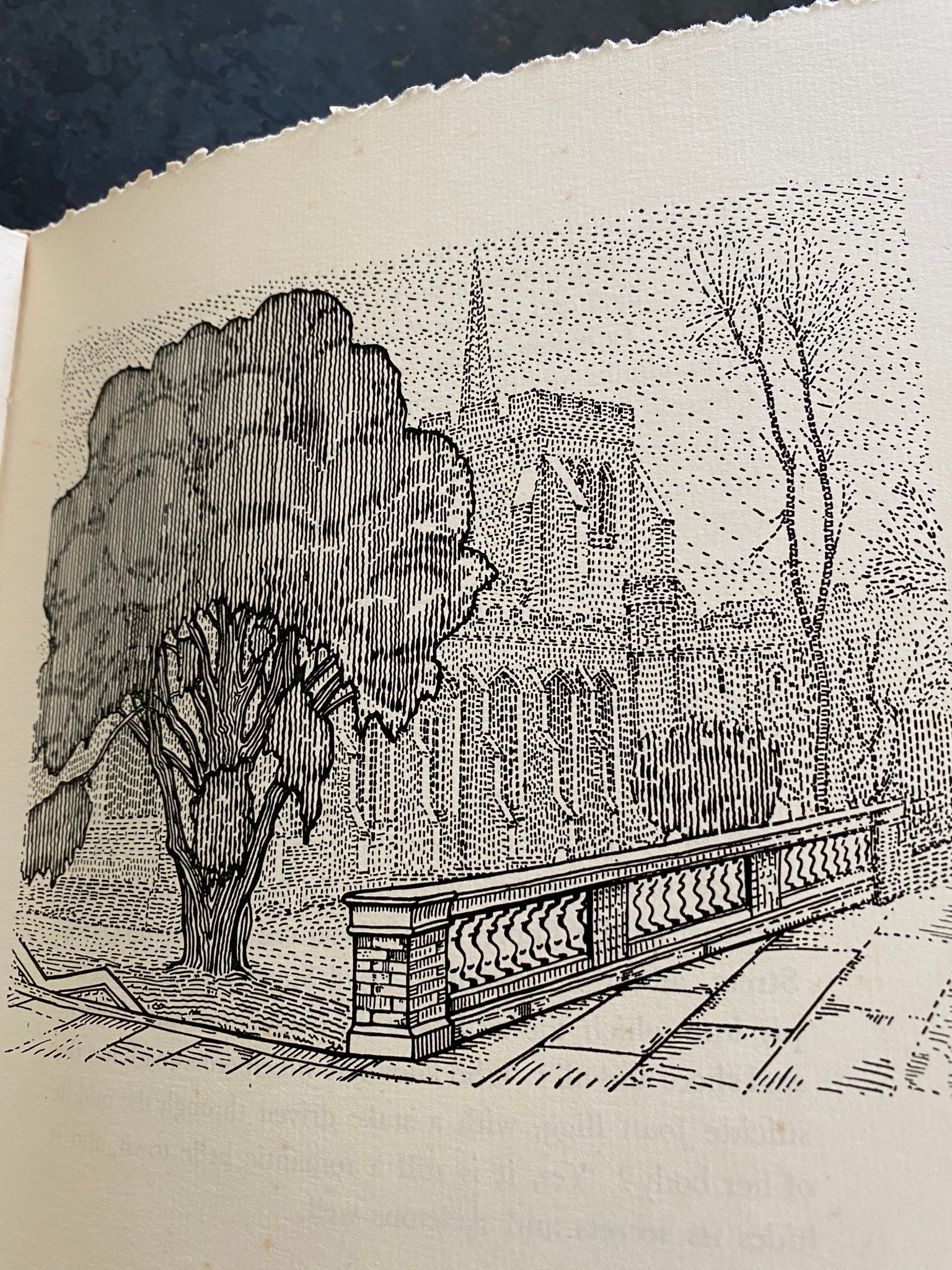

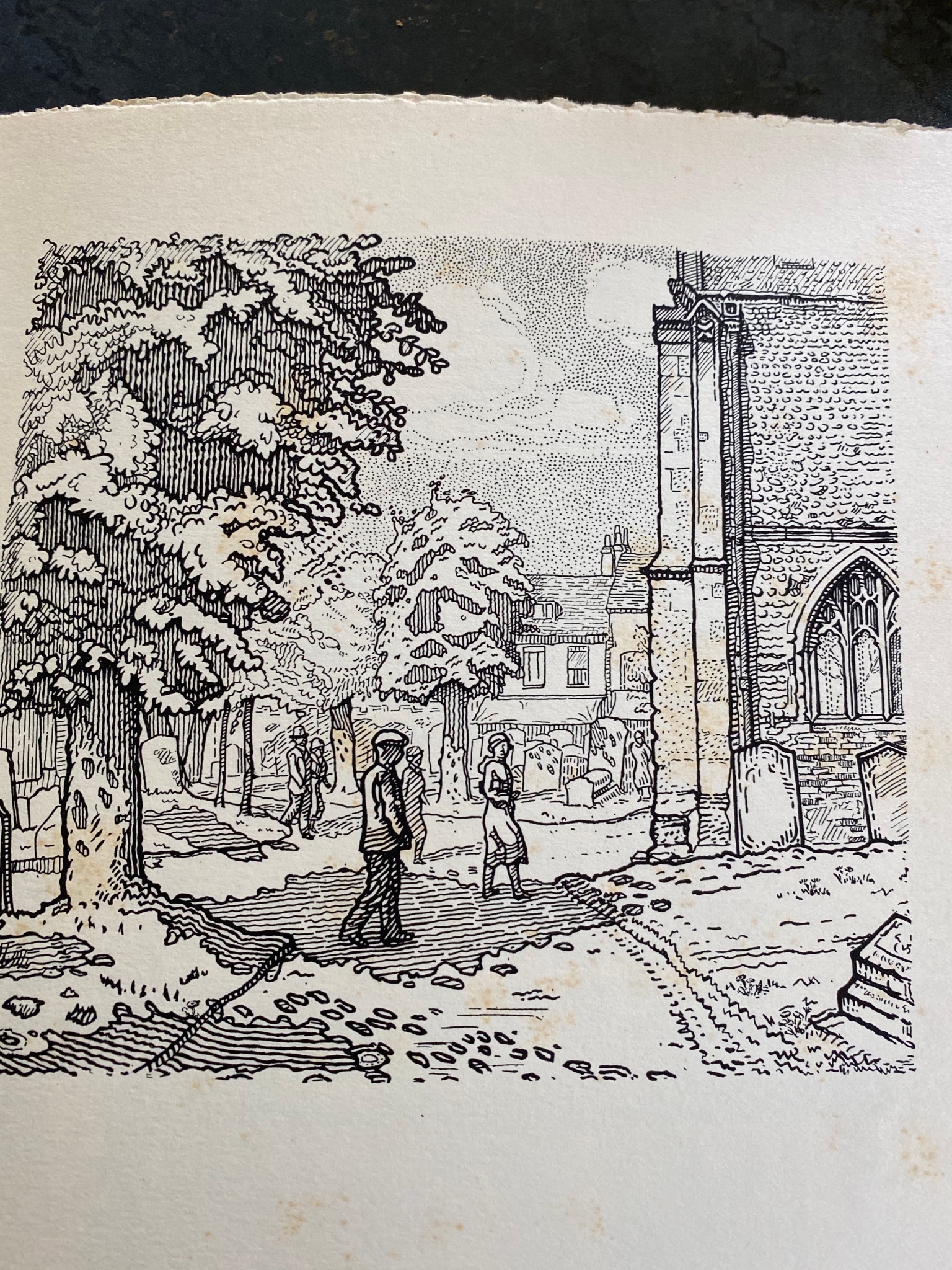

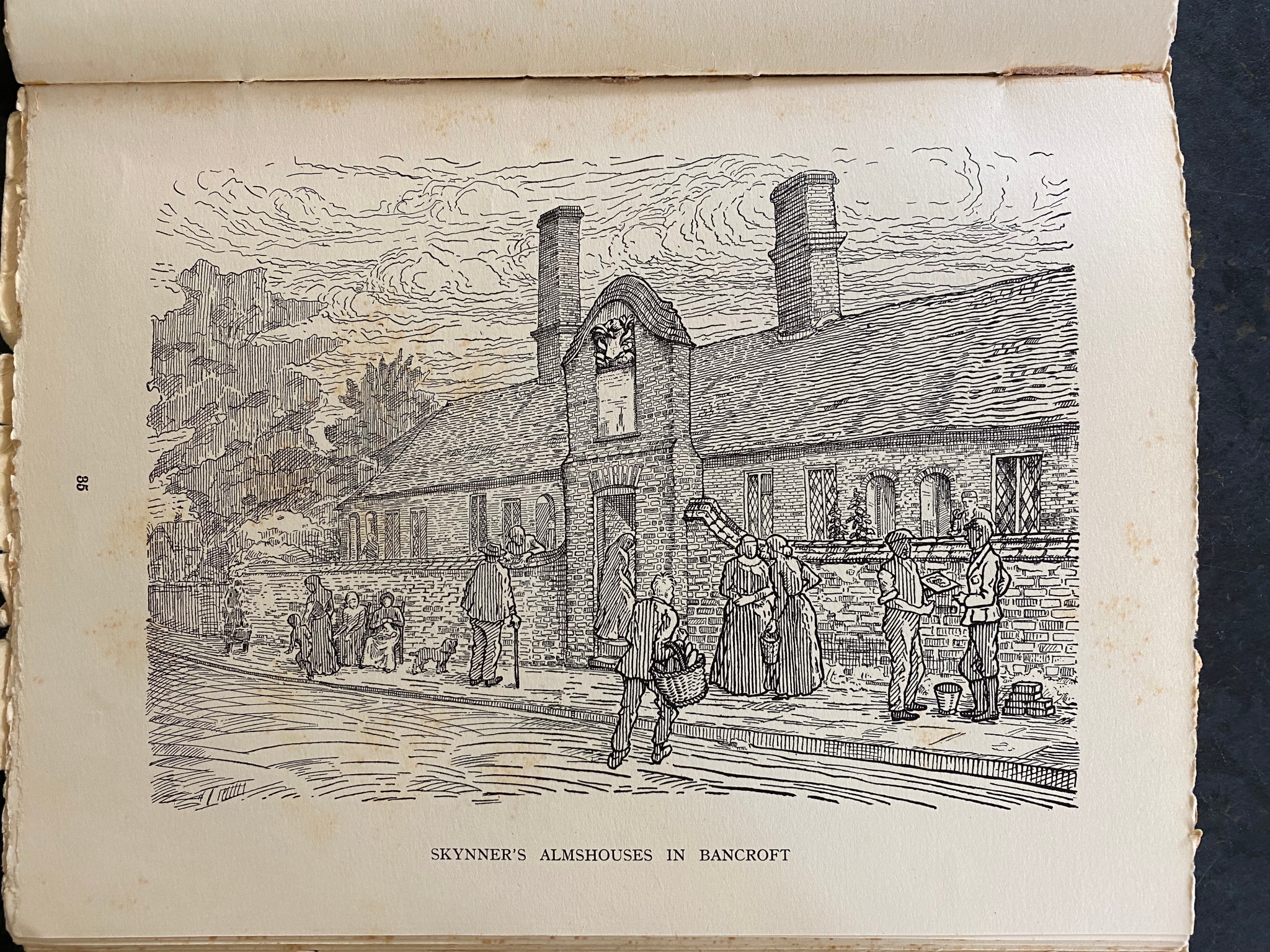

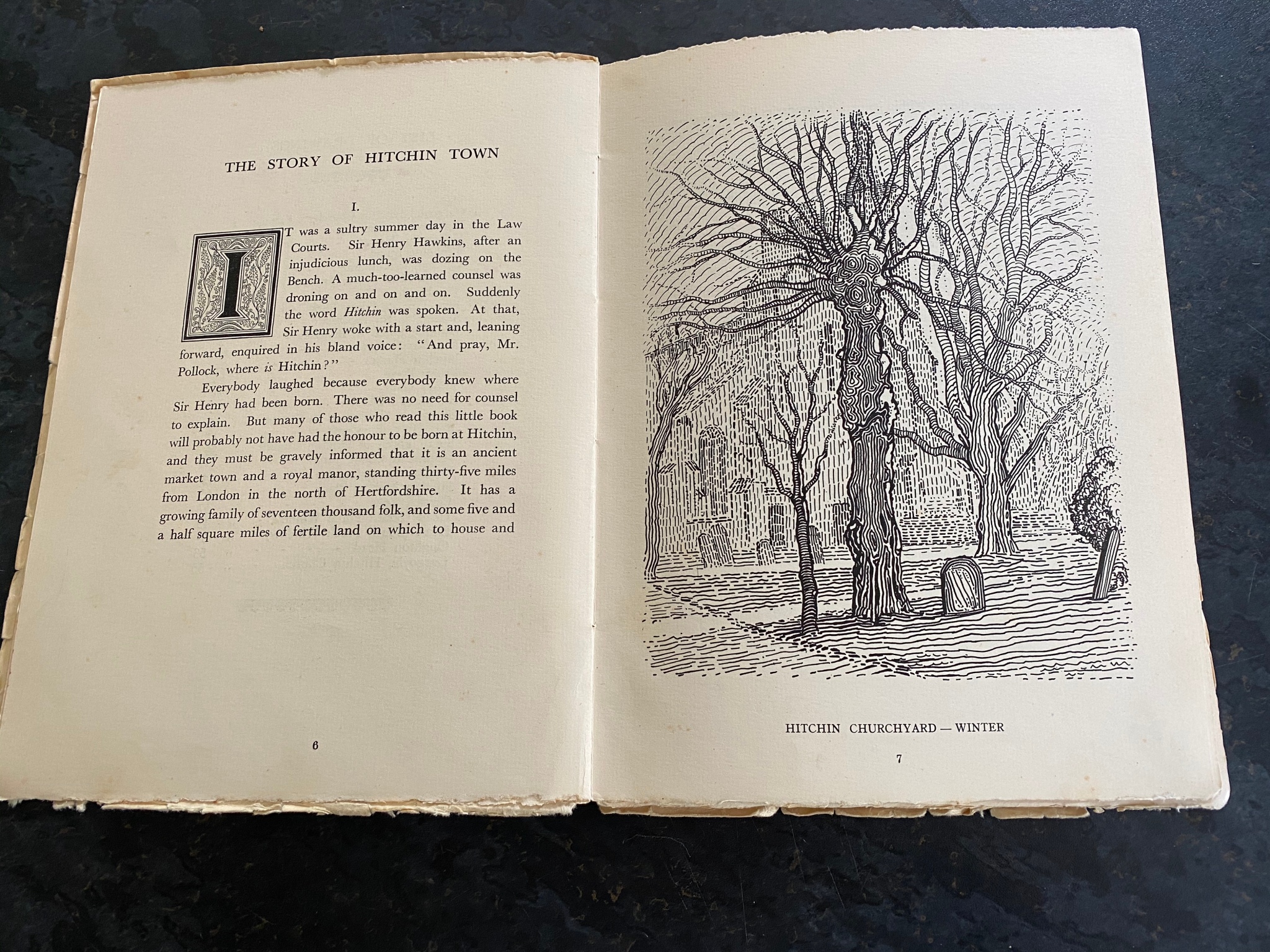

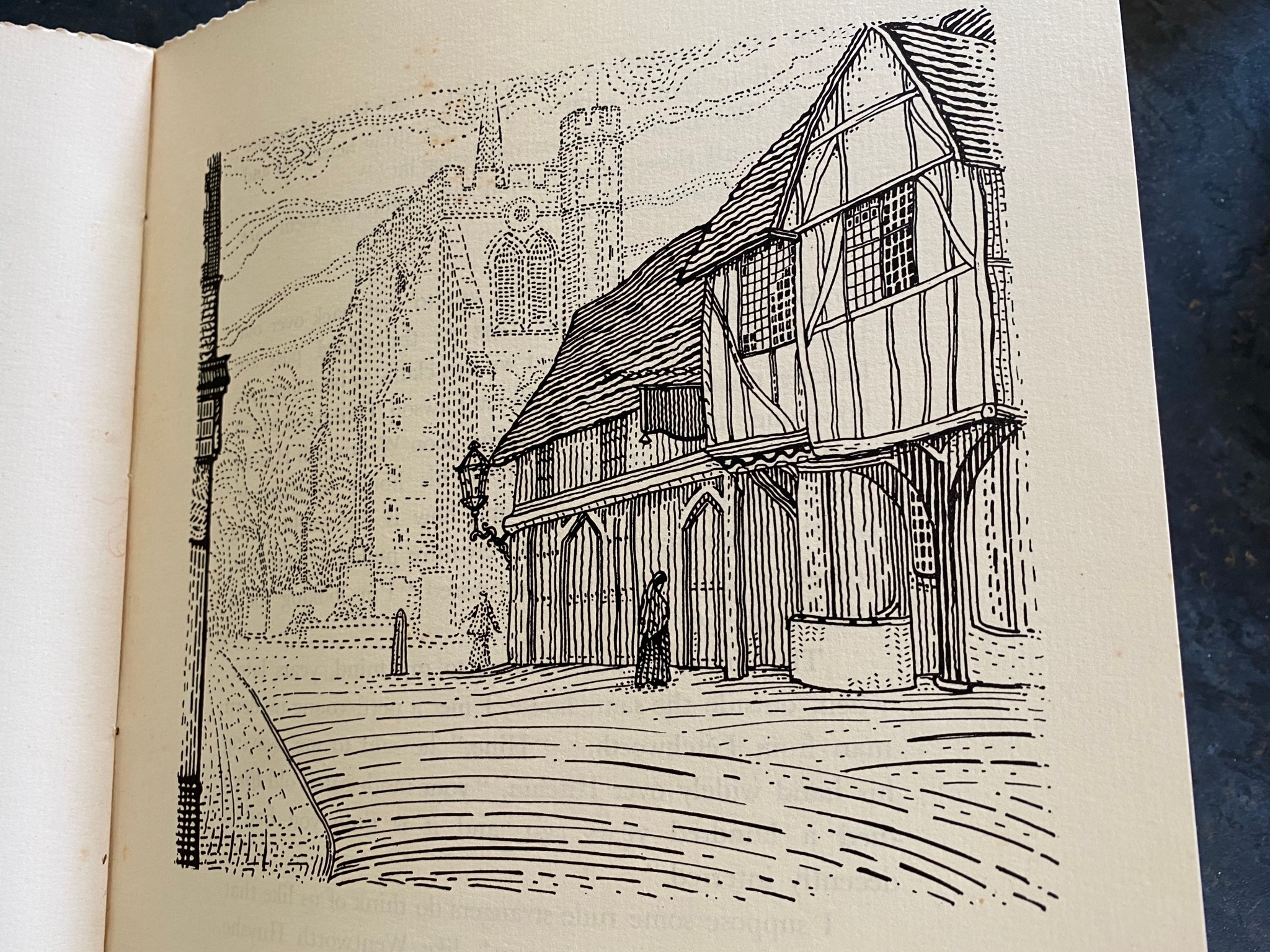

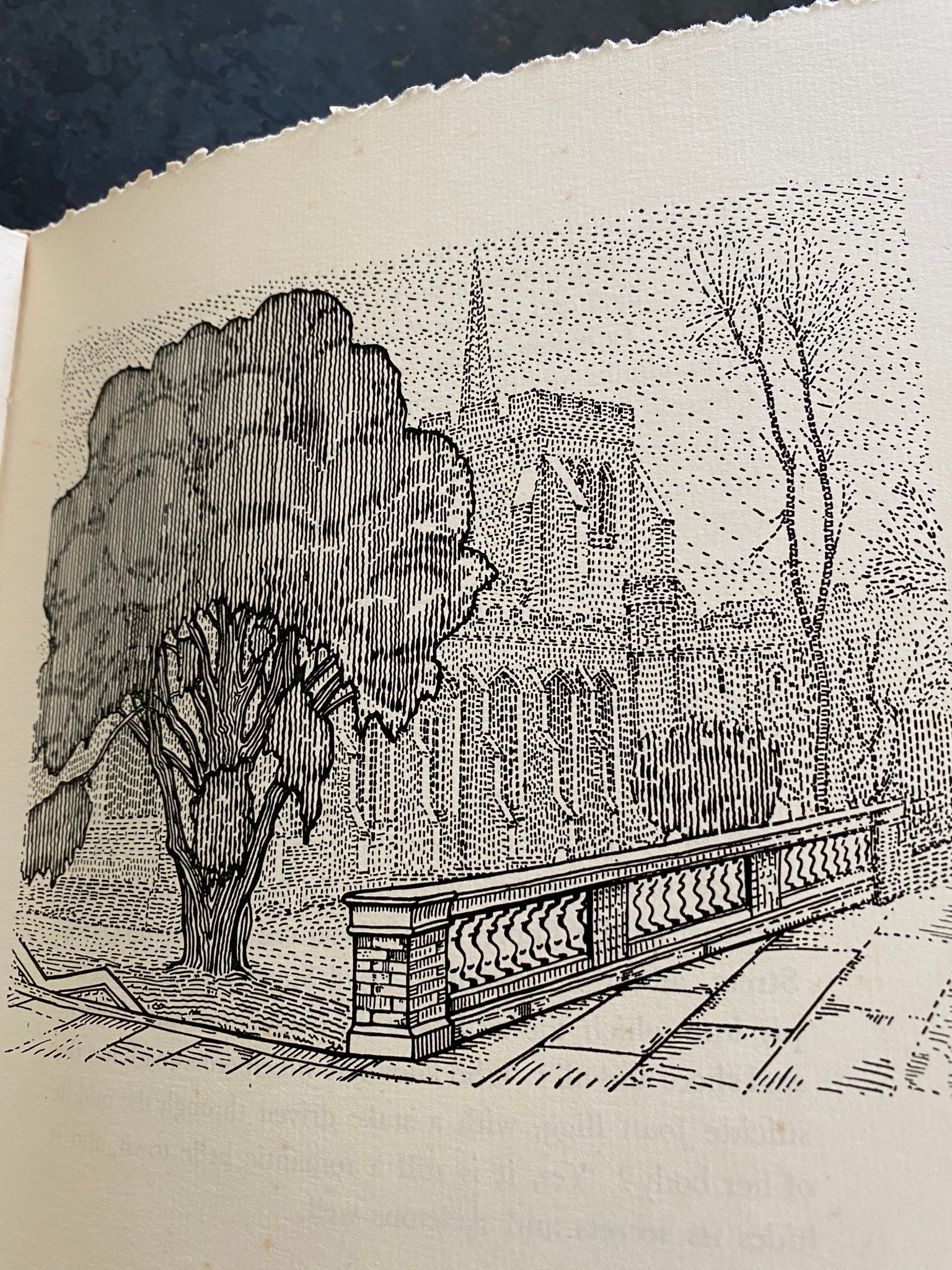

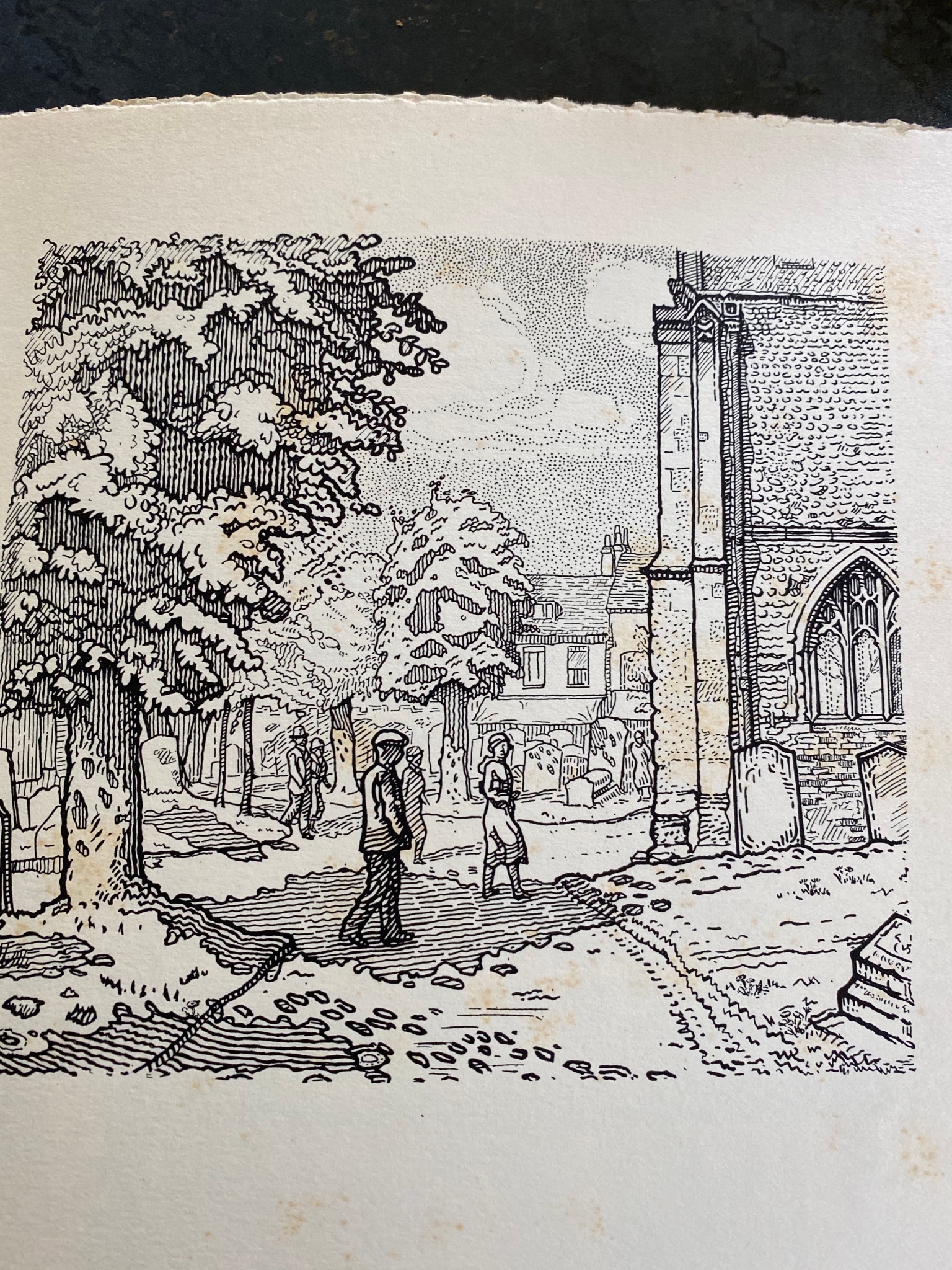

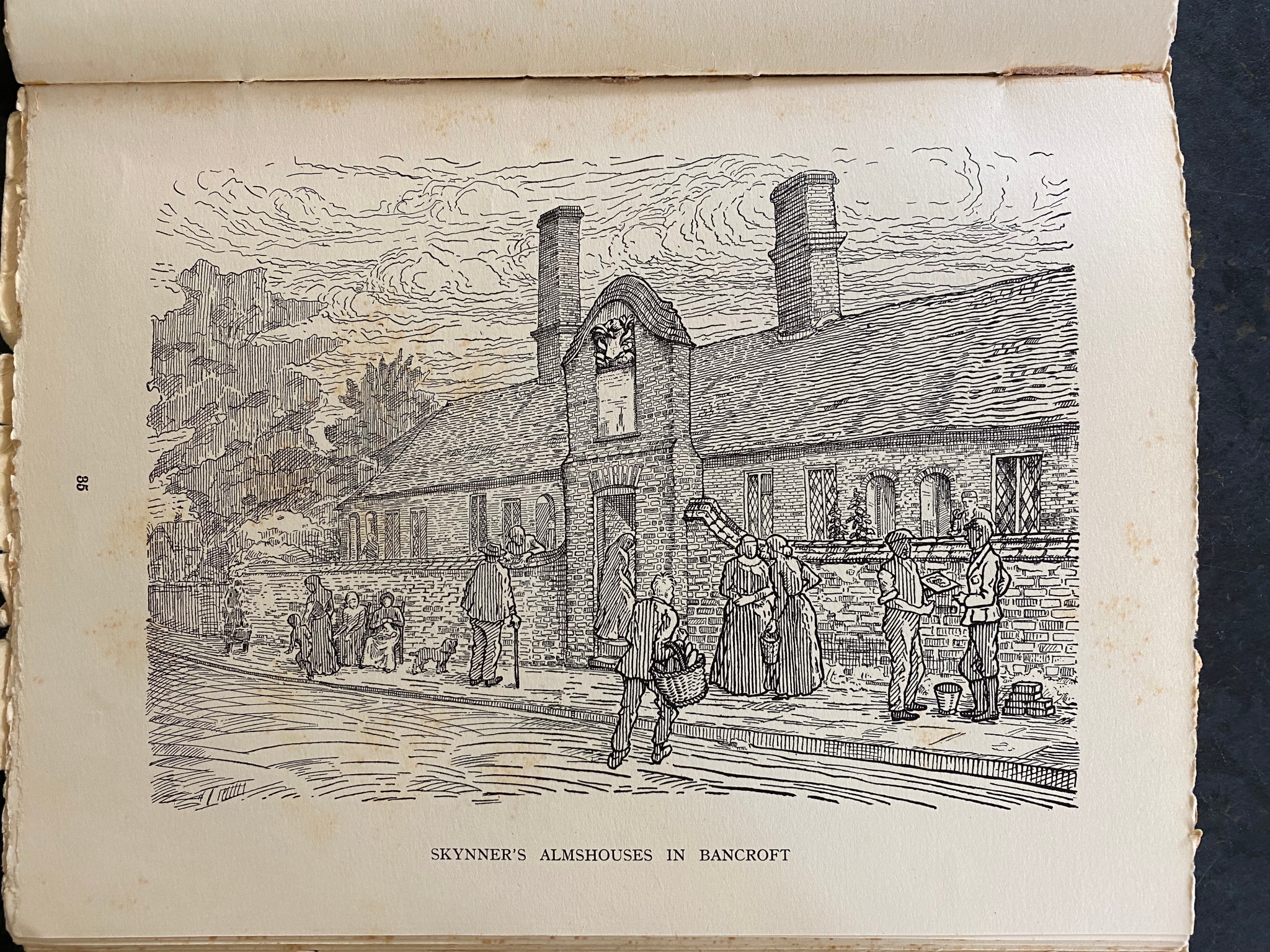

Printed in a large format monochrome design, the book is little more than 50 pages in length, of which half are taken up with Hine’s text, with the facing pages being devoted to Ceunis’ illustrations, simple drawings with line shading. Hine invites his readers to ‘turn over the sketches in this little book – the work of an artist born in a foreign land and so, with undulled vision, the more able to capture the surprising qualities in ours’.

Some of Ceunis’ illustrations, such as those of Hitchin Marketplace and St Mary’s church, closely resemble his paintings of the same scenes (see the previous post), and may indeed have been sketches for them. Others capture picturesque corners of the town – a row of houses, or an architectural feature of historical interest. As with Ceunis’ paintings of Hitchin, many of the scenes are still clearly recognisable today.

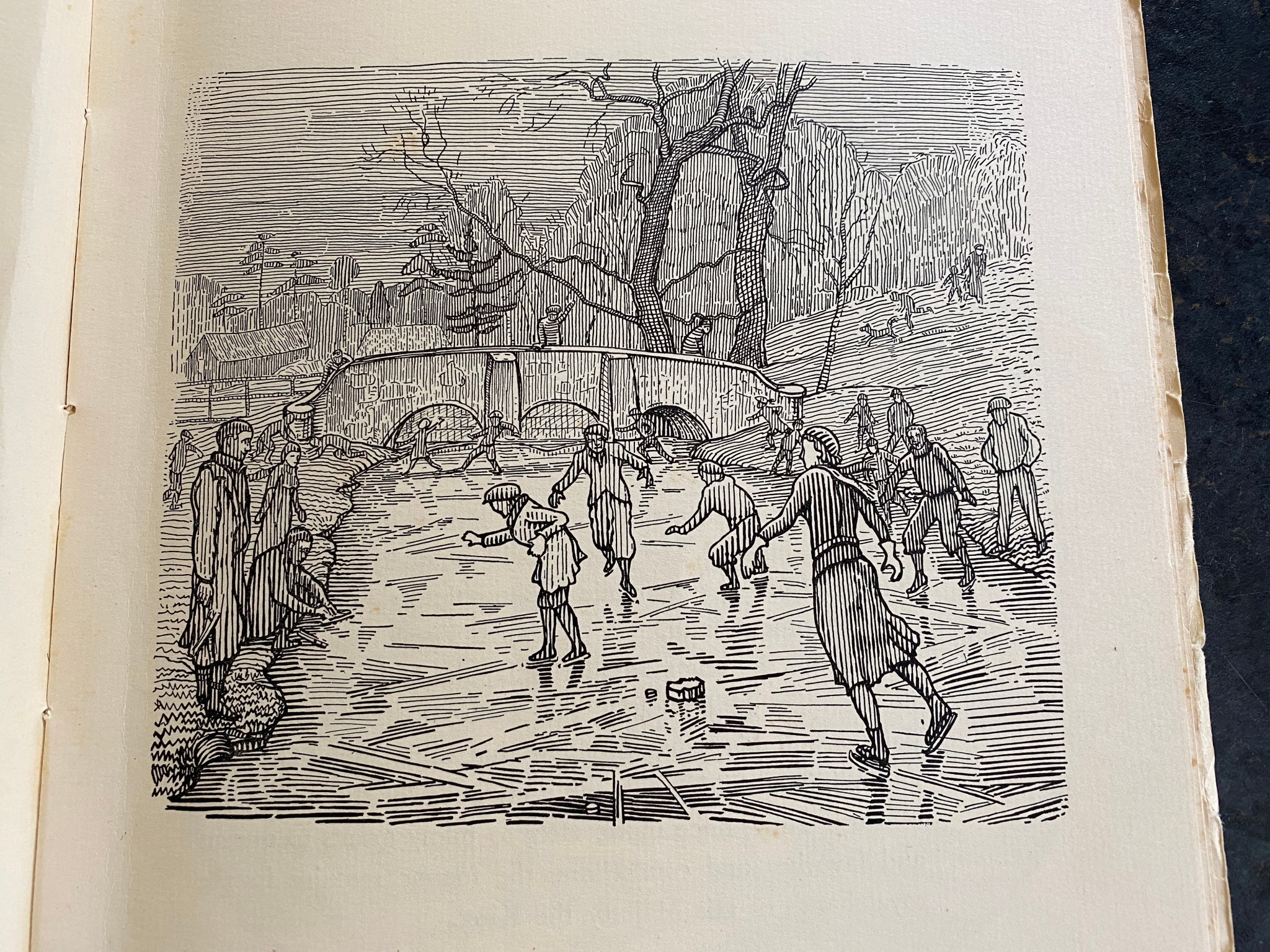

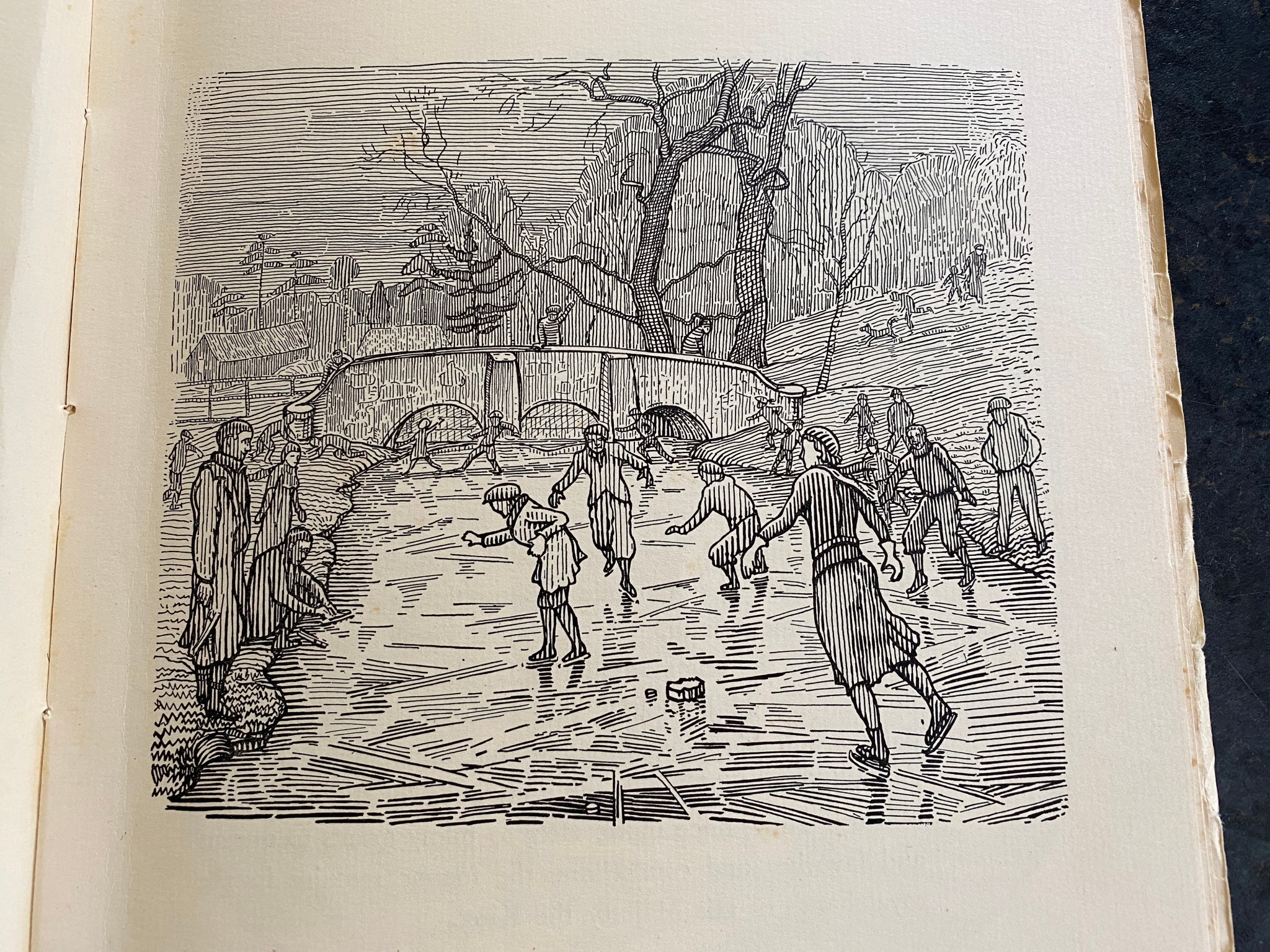

Towards the end of the book, Hine turns his attention to the attractions of the countryside surrounding Hitchin: ‘Just as the country steals into the town, so do we townsmen steal into the country – away to Oughton Head, Gosmore and beyond, St Ippolyts and Minsden Chapel, some of whose allure can be imagined from the lovely drawings of them that grace this book’. Some of Ceunis’ illustrations of these rural scenes are among my favourites in the book. I particularly like his drawing of ‘Skating at St Ippolyts’, perhaps because the bridge over St Ibbs pond, which was installed by a Victorian clergyman nostalgic for his Cambridge college, is a familiar landmark on our walks through the village, though it must be many years since local people skated there.

Interestingly, Reginald Hine had been a friend of F L Griggs, another artist associated with Hitchin, who died in 1938, around the time that The Story of Hitchin was published. Griggs, a draughtsman and illustrator closely associated with the late flowering of the Arts and Crafts movement, also created some memorable drawings of scenes in his native Hertfordshire, illustrating the ‘Highways and Byways’ series. I’ve written about Griggs elsewhere.

Sadly, Reginald Hine’s own story had a tragic ending. Suffering from depression, and facing disciplinary action from the Law Society over a mishandled divorce case, he committed suicide by jumping in front of a train at Hitchin station on 14th April 1949. A small garden with an inset portrait plaque in Lower Tilehouse Street in Hitchin is dedicated to his memory (photograph via wikipedia.org).