I’ve written before about Gerard Ceunis’ key role in the launch of the Belgian literary magazine Iris, which first appeared in 1907. Thanks to the excellent dbnl website, and specifically its digital version of Raymond Vervliet‘s De literaire manifesten van het fin de siècle in de Zuidnederlandse periodieken 1878-1914 , I’ve managed to track down a copy of the magazine’s artistic manifesto, published in its second issue, in March 1908 – and written by Ceunis himself.

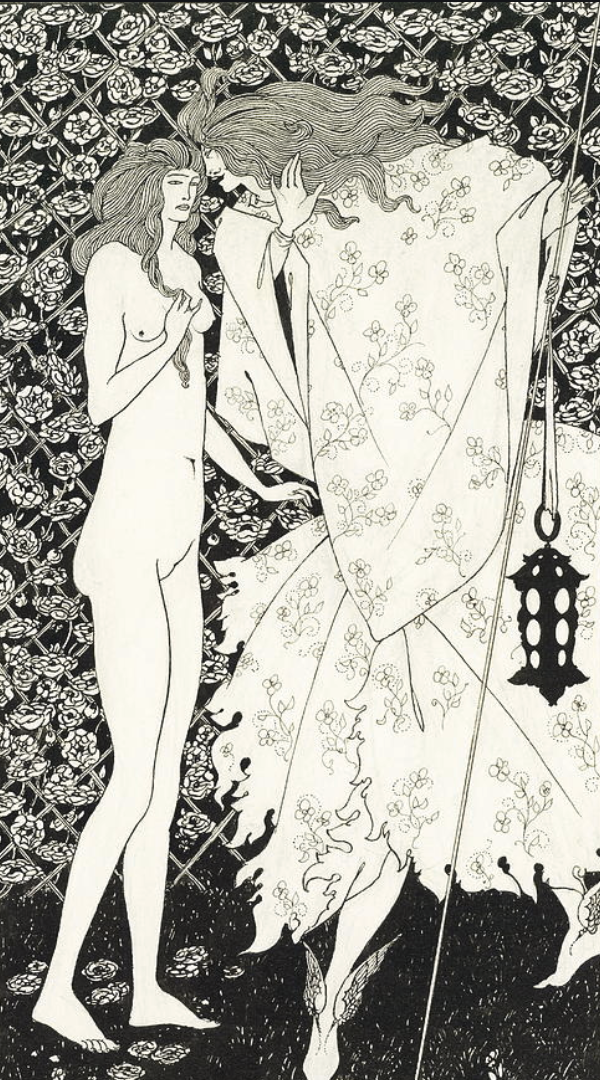

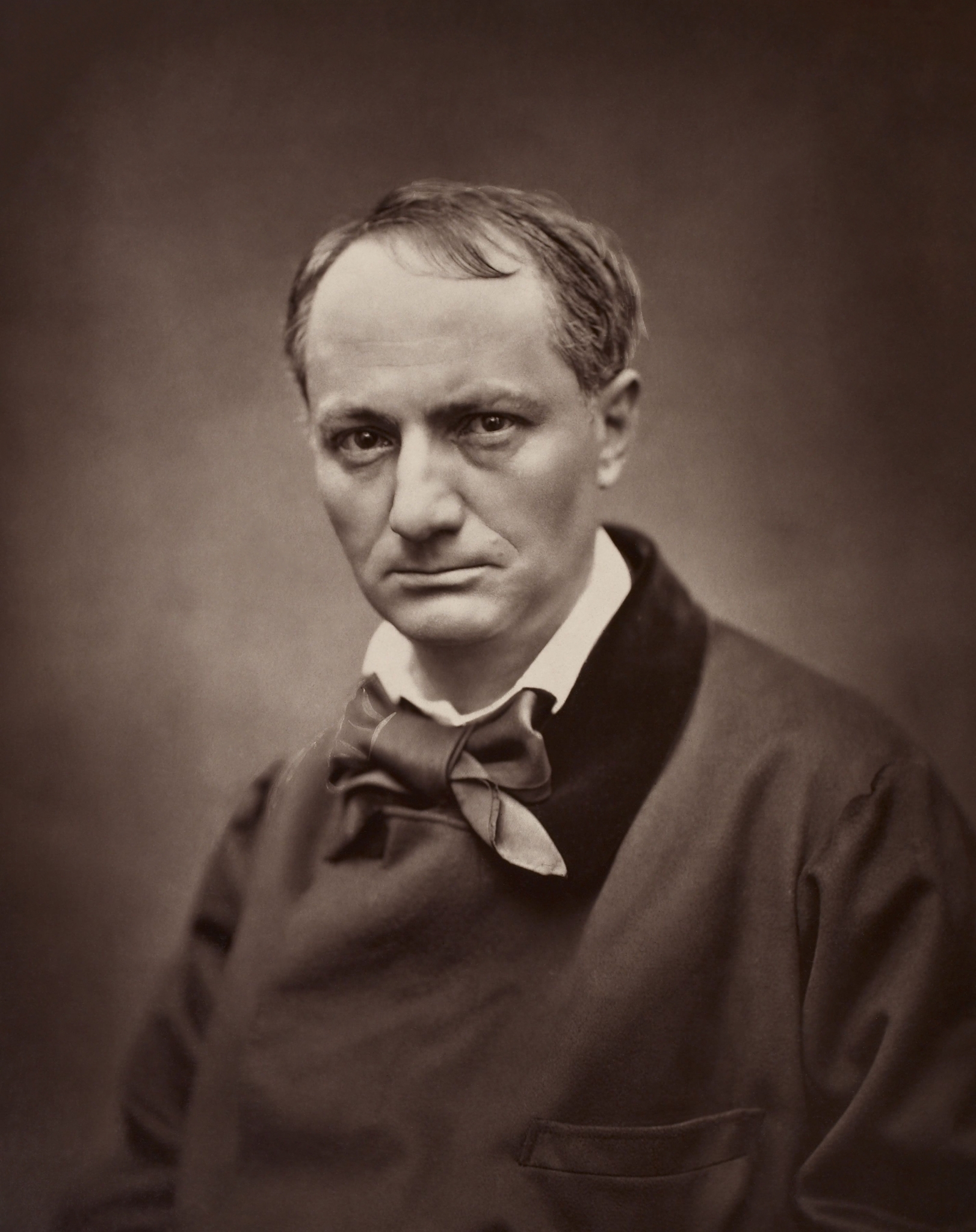

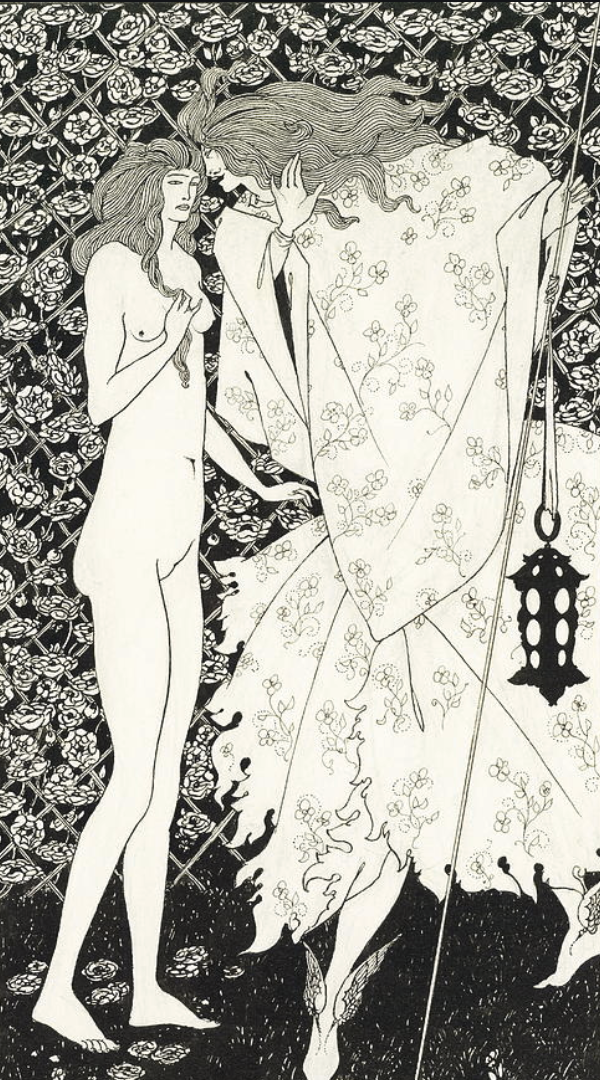

The manifesto provides us with a useful insight into the young artist and writer’s aesthetic beliefs, confirming the suspicions aroused by reading his early poetry and plays, that he was strongly influenced by the French Symbolist poets, especially Baudelaire, whose Les Fleurs du Mal he quotes here, and by the ‘decadent’ art of Aubrey Beardsley and others. Like the Aesthetes of the late-nineteenth-century, Ceunis makes the case for an art that is sensual, dreamy and mystical, and for a literature that aspires to the condition of music.

Producing a readable English version of this text, depending largely on Google Translate, has presented me with a number of difficulties. As in his poems, Ceunis tends to coin new words and yoke familiar words together in unfamiliar combinations. Some of the words he uses don’t seem to be in any standard Dutch dictionary – perhaps they are particularly Flemish? – and in many cases I have had to hazard a guess at the meaning. In other cases, where a word has a number of alternative meanings, it is sometimes unclear which meaning the writer intends. I faced particularly difficulty with the word luwtje which can be translated as ‘lee’, or ‘shade’, or ‘shelter’, but in other cases as ‘gem’, and when combined with streel as ‘caress’. However, I hope that, despite these drawbacks, my version gives a sense of the main lines of Ceunis’ argument, and a flavour of his idiosyncratic literary style.

‘Art’ by Gerard Ceunis

Come, feathery gem [pluim-luwtje], caress my hair, and bring me soft scents – scents of the land and of heather – scents that sing with colours. And that massive movement and noisy bellowing of strong winds? Has that great force gone away then? No! that giant thing still rumbles on, perhaps more powerful than ever perhaps, but … the wild sighs of the wind float silently between, in, above and below it, and the great forces flying by may from time to have been so bold as to cast snooty [orig. in German: hochnäsig] looks and laugh mockingly at that faintly sentimental dream, but now they have become better friends. They know each other well; and that is why I can allow myself to be comforted by caresses [streelluwtjes], without these great loebers [?] ruining my pleasure.

And these gems [luwtjes] delight us so much and so often now in our modern art; that soft, inward, intimate note sings so much from the new work of today that we may hope to see the scent of a fine soul slowly rising to the heights, into the distance beyond the merely human; so that ‘art’ becomes an inappropriate word and we feel the need for a new word. We would call it music if ‘music’ had only remained a little more aristocratic.

They know each other, so these gentle caresses [streelluwtjes] and these strong winds will blow together across the earth and respect each other. But the latter needed the greater force in order to be born, and groaned with strong life-consciousness and with mighty skill, while the former, by contrast, were of fine-scented air, were born of a more subtle feeling, more deeply intense in the soul, like fine dream-enticing perfume.

Let us call a work of violent movements and loud cries grand and majestic, because it arouses our admiration and awe at the massive effort required for its creation, but on the highest level of art we will place those images and chants that resonate with the eccentric and beautiful depths of the soul.

Art has only one goal: to give us the highest pleasure and the most intense desire. Only that!

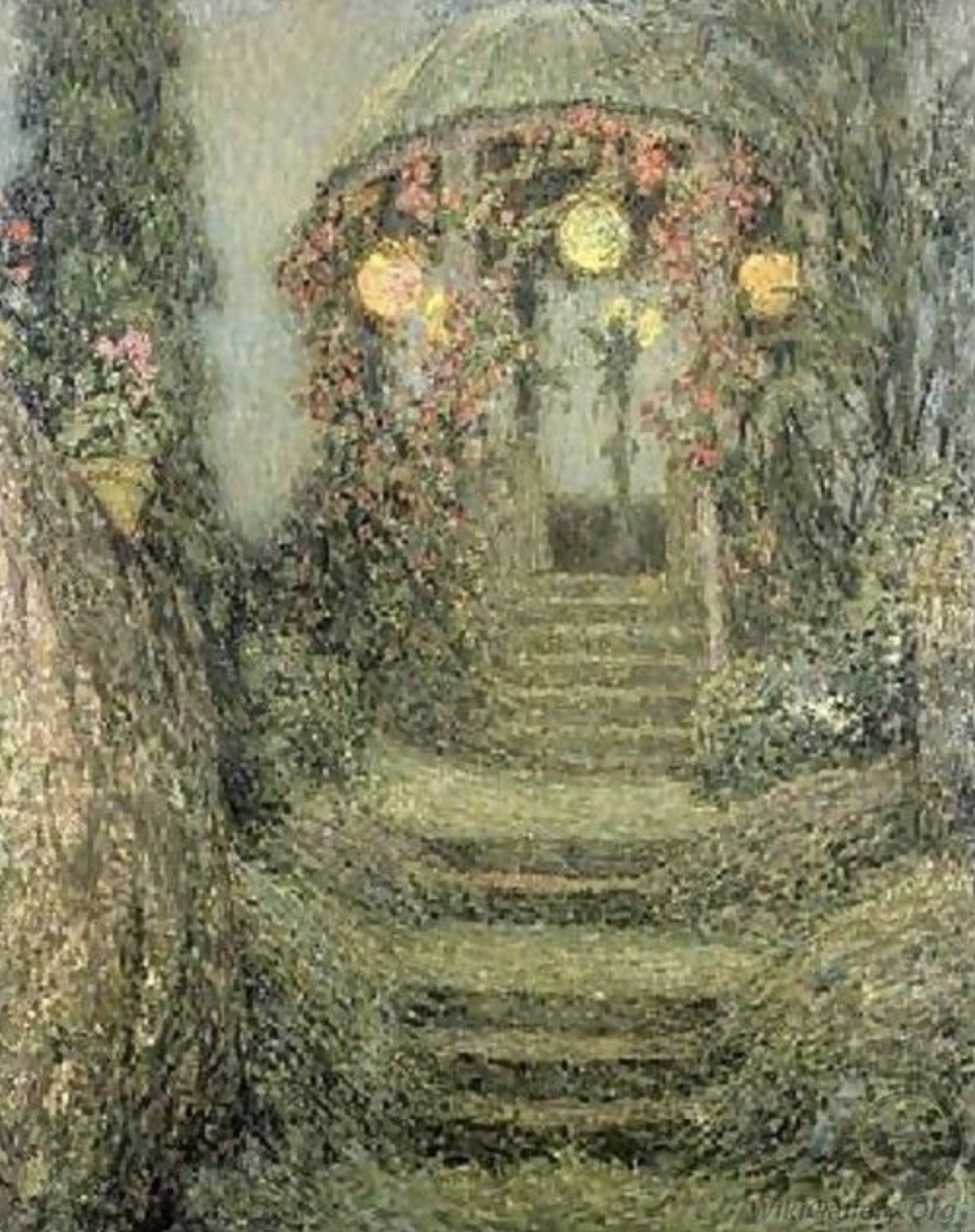

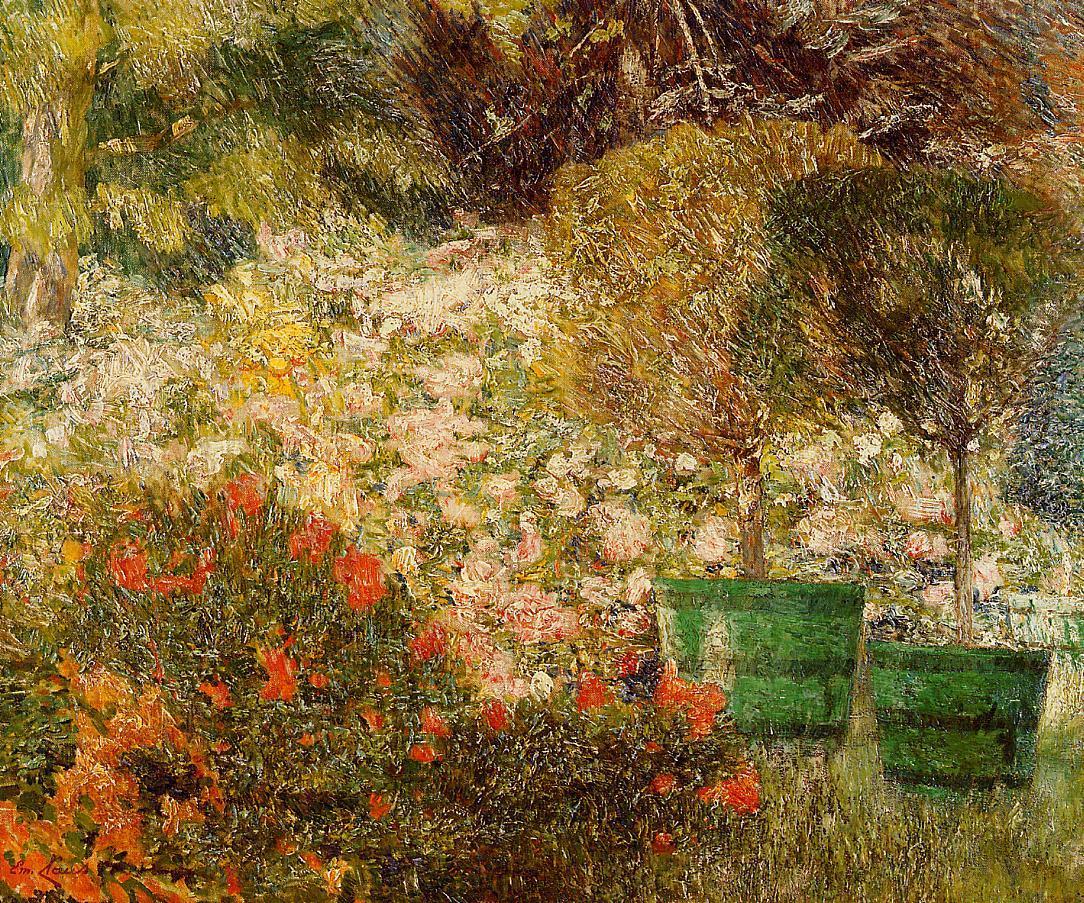

Henri Eugène Augustin Le Sidaner, ‘The Illuminated Pavilion’ (via wikipedia.org)

And art is all life, seen, dreamed, dreamt [gedroomd, verdroomd,], sifted, by our soul. And the artist is indeed the happy man who will taste the first and deepest impression of his art, even he does not succeed in articulating his feelings or his thoughts. For a frail melancholy smile, a dream-glimpse of the eyes, of deep pools [een droom-blik uit oogen, van diepe meren], aren’t these the most delicious poems without words, without creation? We carry the essence of art, that is to say the feeling, with us everywhere in our shy soul and we ask for no more massive forces than patience-work to stimulate the pleasure-ground, to bring about fine emotions through art-work.

And the art-creations of men will certainly arouse in us admiration for their genius and talent, but will only move us to exquisite pleasure or ecstasy, to the extent that the work, whether great or small, has intensity of life and feeling.

But, I hear it said, without creation there is no art, so that creation is …

Of course! without creation one cannot arouse emotion, but without an inner feeling one cannot create. Every artist, before putting his hand to the work, has been struck by an impression. That is his greatest achievement. The rest is vanity, or greatness, as people say.

Although art is: to embody, the emotion that stimulated and compelled the act of creation, this is its god and if not ‘art’ itself, then it is something more exalted.

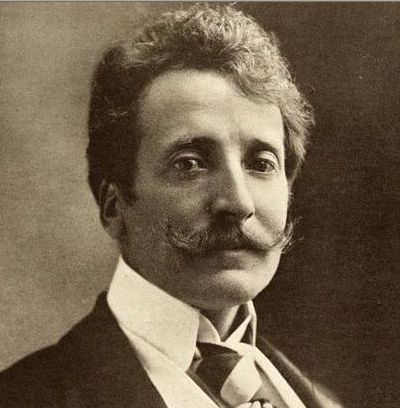

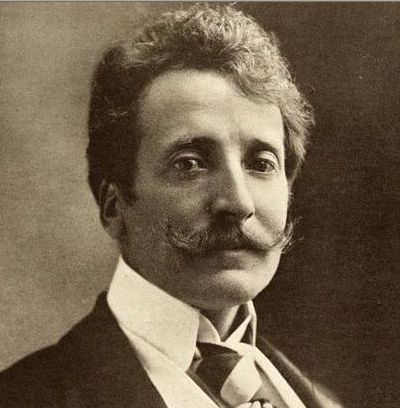

So as I said of this fragile, intangible soulful art, we hope to see its scent rising to such a height, so far beyond the merely human, like Baudelaire, like Aubrey Beardsley, like Lautréamont, and to go from hell to heaven, like Memling, like Tinel, and, moving on to the more healthy, like Beethoven, like Whistler, like Sidaner, like Storm.

Aubrey Beardsley, ‘The Mysterious Rose Garden’, 1895

To think that it is now called decadence, effeminateness, morbidness or something like that, something which can cause harm to such a heavenly thing as art, to the ideal, to the sublime and to the supreme, that is to say to what intoxicates us with aesthetic pleasure, to what bestows upon us the highest spiritual desire?

Now, we are not Greeks, and neither wisdom nor virtue will be the essence of our art.

Civilization takes such astonishing steps forward, and art purifies itself. Wisdom and virtue are almost a whole world away, and now art can walk freely without having to preach morals, and without being tempted in that direction. And the down-to-earth man is satisfied now, he thinks his position is high enough (every healthy man is subject to dizziness), but he thinks that something that still needs to be cleared away is that sickly, sad-melancholy face in art.

Decadents – as one calls those sensitive souls inclined to sickness – and mystics, will always guarantee me the unworldliness, which I find in their work, as well as the delicate pleasure they seek to give us.

Not for you, down-to-earth man – for you, it has to be healthy, full of life, isn’t that right? You are right, you have much more wit and cleverness than me, but I beg you, do not touch my soul with your coarse, earthy hands.

It is just as stupid to say that a work is naïve, or decadent, and therefore of lesser quality. But people are so dignified, genteel. The platonic is a little too clean, naive, oh so naive, and decadence is a little too sickly for them. Now, the general public would prefer healthy chunks of life, full of lively natural energy.

Music has surpassed all pretensions to be art. Music is infinity, the absolute, eternal beauty, the poetry of the softly floating, indefinable feeling, of being a divine soul.

Poetry, prose, painting, drama, in short, all kinds of art want to sing, and unconsciously aspire to the purple dreamy air where music lives. That is their noble, their highest art. And in order to reach that height, personality, talent and technique will have to combine so harmoniously in every way so that one does not see the words, hear the sounds or notice the colours, but simply feels what the artist felt.

The means of artistic expression is only a side issue. By the deep-intense feeling of the artist, who wants to remove all matière from his work, to let the intimate soul-felt image appear in all the serenity of impalpable poetry, as it floats within him, all means, all expressions join each other and rise dreamingly to that height, to the tactile delicacy of something more than merely architectural music.

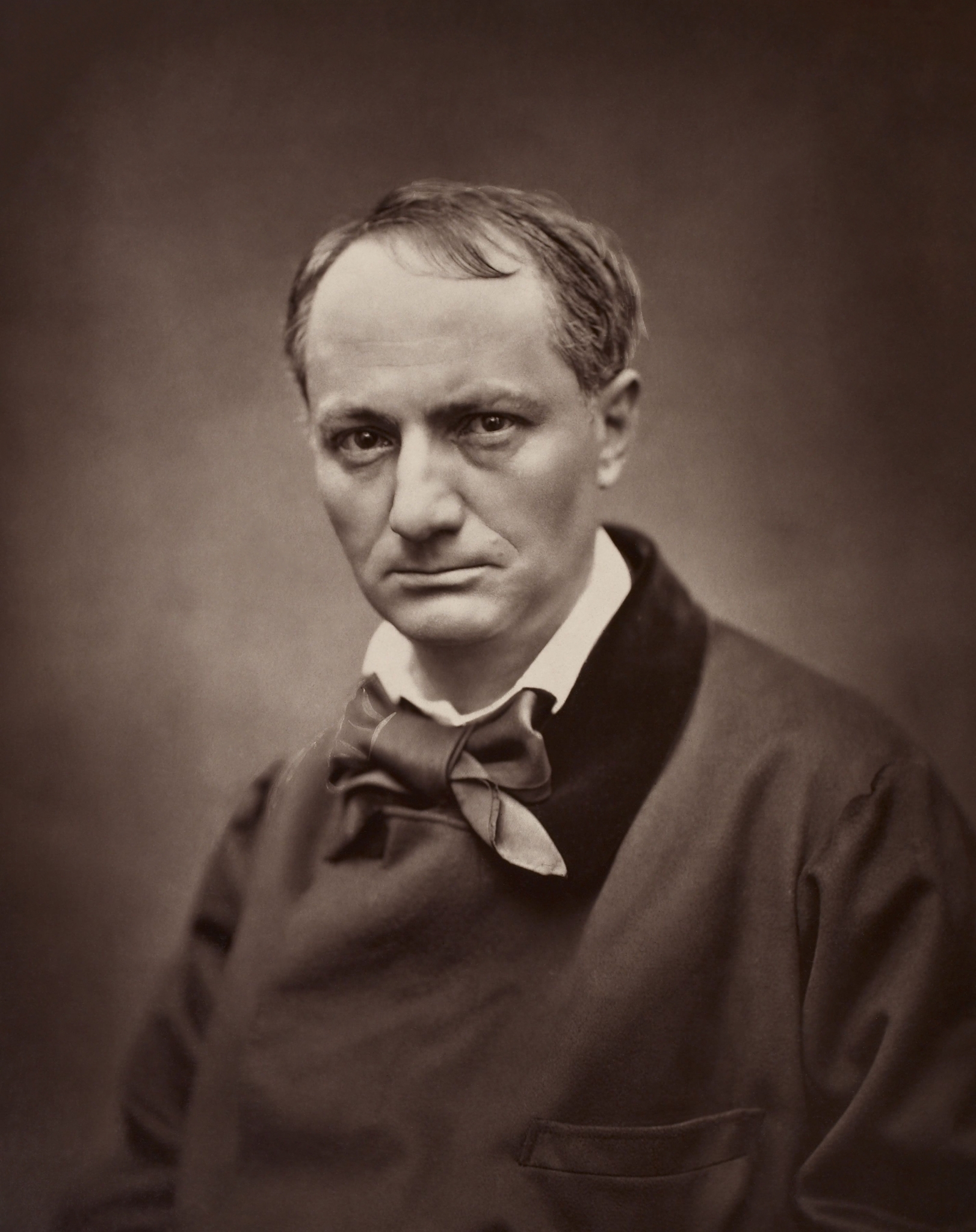

Émile Claus, ‘A Corner of my Garden’ , 1904 (via wikipedia.org)

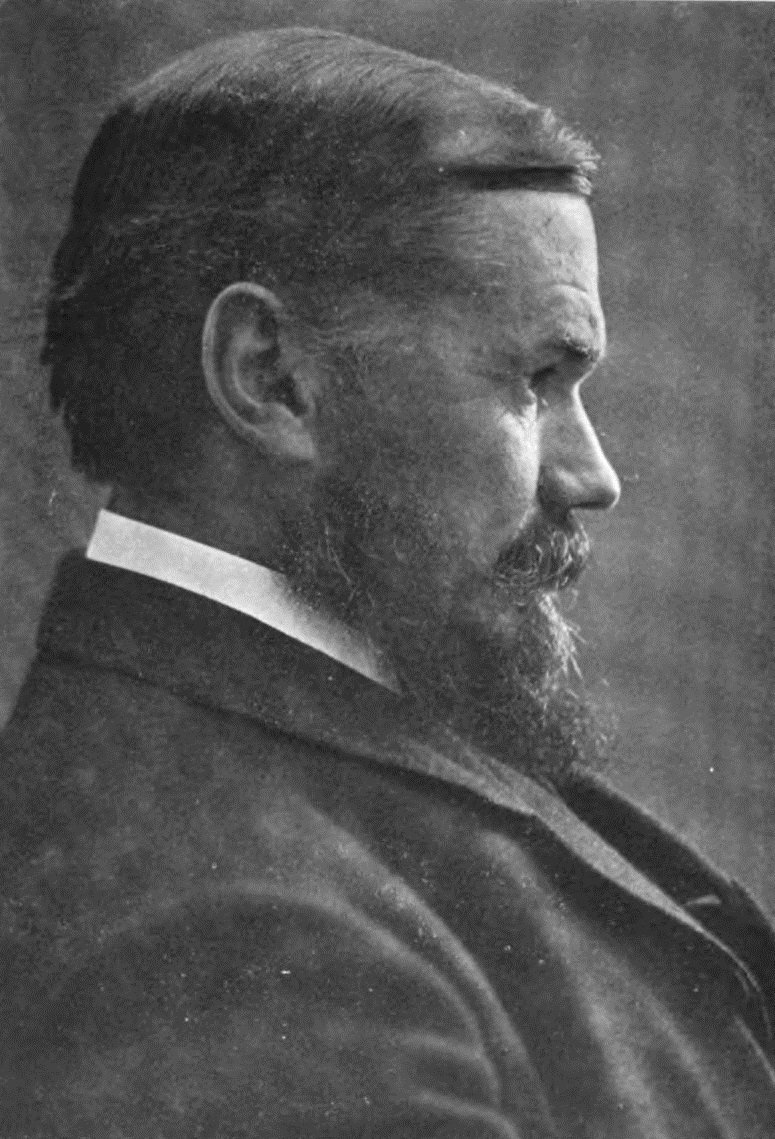

And we do not want to see the means of expression to begin with, but rather the embodied image, the art-expressed impression. And so we mention Baudelaire and Aubrey Beardsley in one breath, so many works by the harmonist Claus suggest to us Beethoven’s Pastorale, and so we experience Le Sidaner and G. Rodenbach like a melancholic poem.

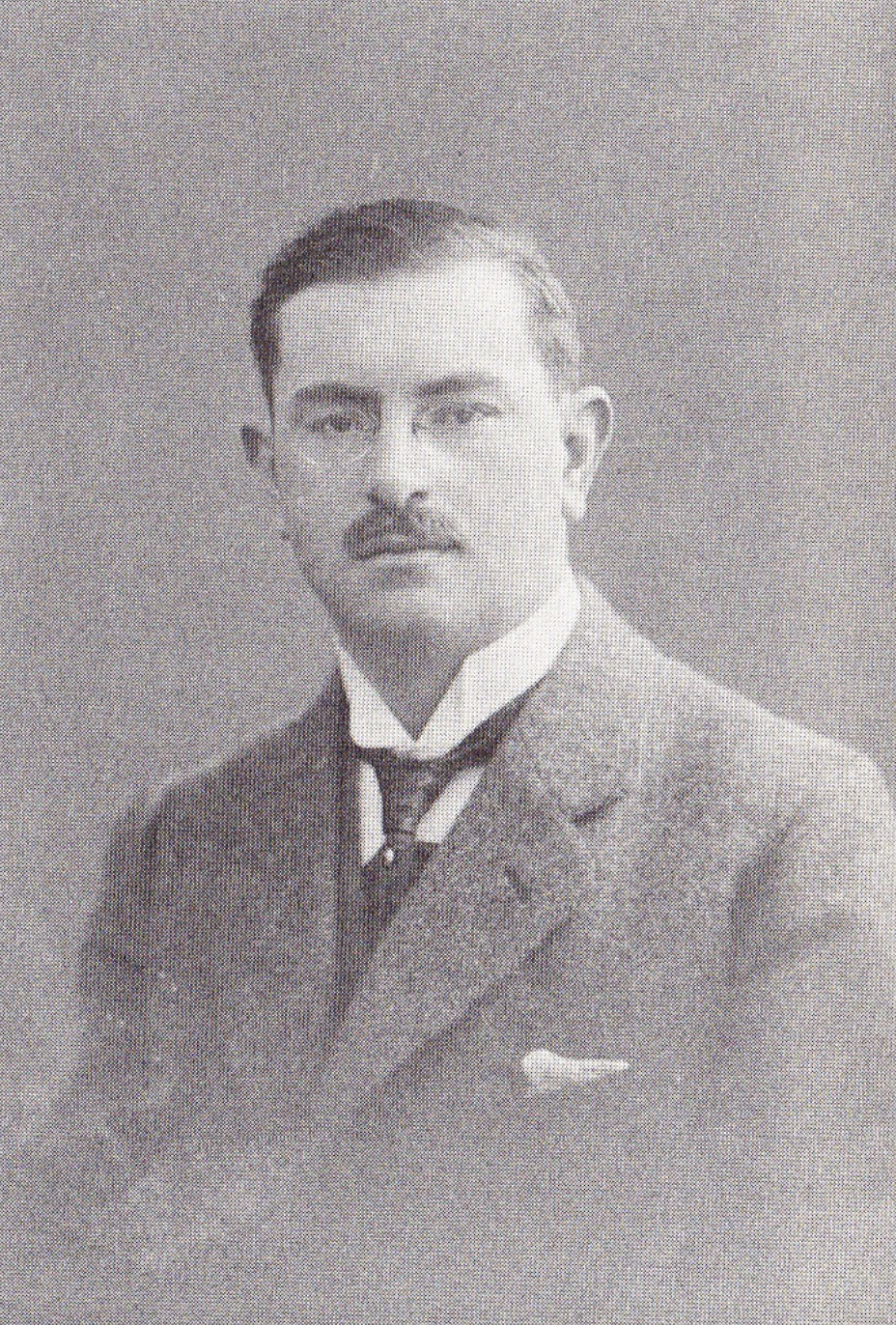

Belgian Symbolist poet George Rodenbach (1855 – 1898), via wikipedia.org

And just as a symphony sings out our wonderful dream-pleasure, a colour symphony can generate the same desire in us. A tune can make us smell; perfume will propel sounds to us; tones and sounds are both sung; all the arts are transformed into misty opulence, rising in the dream-air like soft scents and floating there swathed like a divine thing – like God – enveloped and adorned with the lofty garment of music.

Étienne Carjat, ‘Portrait of Charles Baudelaire’, 1863 (via wikipedia.org)

Now that we are attempting to move towards a higher art, into a fineness of feeling, with poetry and music gradually growing together or rather, now that the caresses [or soft gems? streel-luwtjes] are increasingly being recognised, now that poetry is actually becoming more poetic, and now that the poet is also deriving his songs from prose-art and from painting, so now the need for a harmonious bringing together of the different kinds of art will gradually become more apparent to those who are sensitive and especially to the dillettantes.

As Baudelaire told us in his famous poem:

Les parfums, les couleurs, et les sons se répondent

Il est des parfums frais comme des chairs d’enfant.

Many articles about ‘La fusion de l’art’ have been published. It has not yet become a reality. Some defenders of the idea think that it must be accomplished in the theatre, others argue that advancing such a thought is naive and utopian.

Those arguing for and against are unaware that a completely harmonious fusion in art has existed in Roman Catholic churches for many centuries, and in synagogues during ceremonial services (1). And in fact a highly idealistic, symbolist, mystical art, with all the side effects of aesthetic opulence.

It may not be naïve to imagine this artistic fusion in the theatre, but it is directly against art. They are waiting are for a time that will never come, in a hall intended to contain the largest number of people. And since this fact will always remain, the ideal is not to be expected from the theatre, at least not in full.

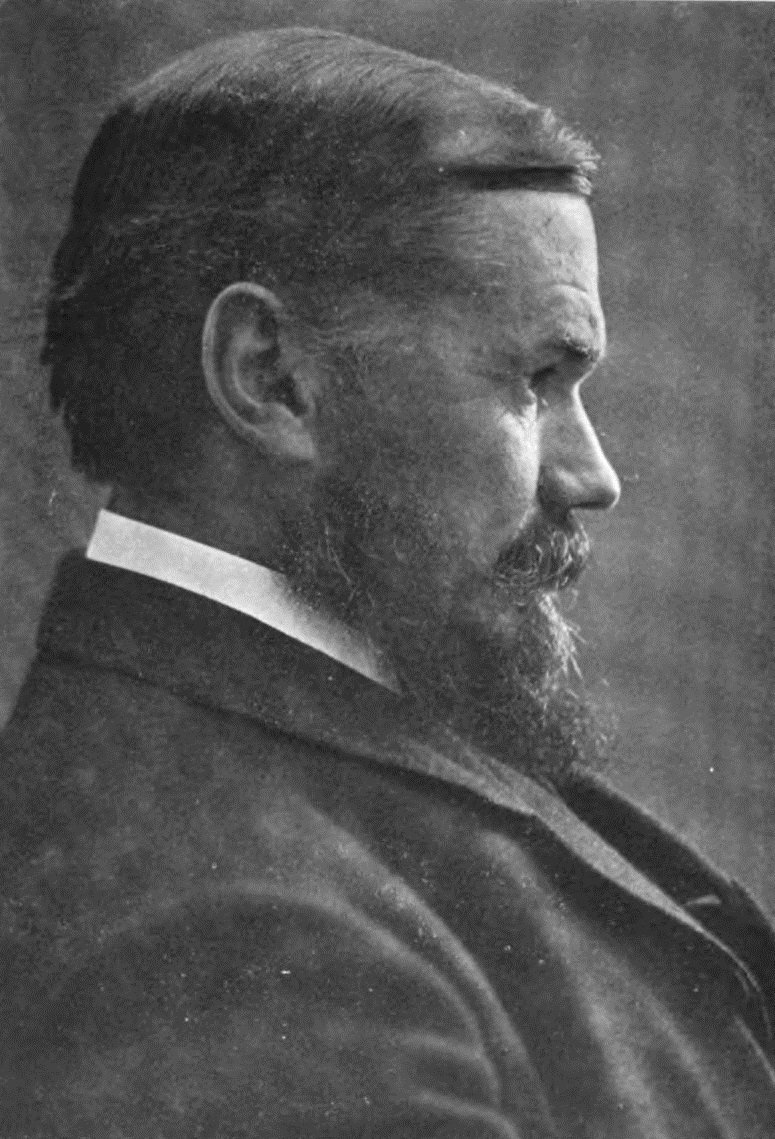

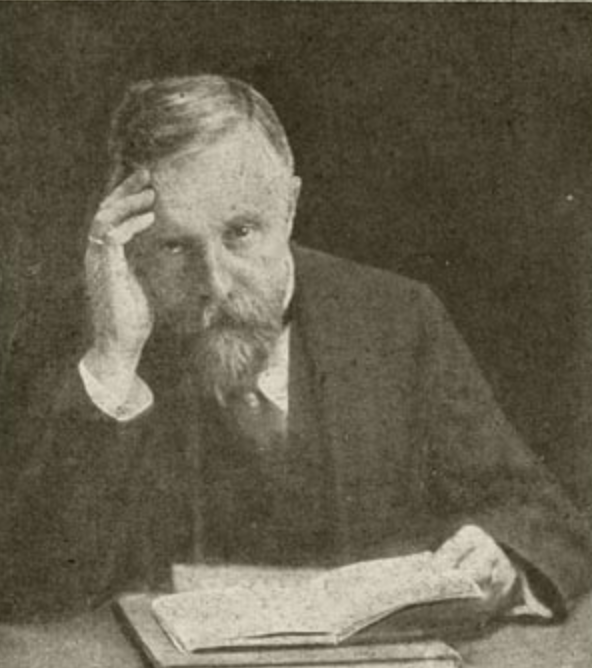

The Dutch writer Frederick van Eeden (1860 – 1932), via wikipedia.org

With Minnestral, Fr[ederik] van Eeden seeks to reform the lyrical drama; but the action must not be suppressed, and must always retain its value. Here, therefore, there is an endeavour to unite two types of art on the stage through music-spectacle, in which music and spoken word should not replace one another, but should alternate in this sense, that the music of the invisible orchestra only sounds, when nothing is spoken, and never drowns out the diction or makes it unclear.

So Mr van Eeden wants to save the word, which is usually lost through music.

In Wagner’s drama we already find action playing an extraordinary role, and yet, where sometimes the divine Wagnerian music conjures magic, word and action decline into a very secondary role. Who indeed needs word and action when he is under the intoxication of the ‘Murmures de la forêt’ from Siegfried?

Arthur Rackham, illustration from ‘Siegfried and the Twilight of the Gods’, 1911

I already said that music surpasses what art is, and seeking to bring the word up to the same level as music can only happen by doing violence to the latter. Either the music will colour and adorn the word, or word and action will enhance the impression of the music. But even more than the word, the impression is heightened by mise en scène, to which the action belongs; word and music by themselves can offer everything, and will never unite into a harmonious whole, in which both arts remain equal.

Therefore it is not desirable for there to be this kind of an art-combination [kunst-vereeniging]. However, Mr. van Eeden seeks merely to alternate the two, so this performance will only further demonstrate whether the alternate incursion of music and word will lead to a harmonious whole, and whether the new self of this music-spectacle will make a more aesthetic impression than opera.

- Iris will discuss this harmonious cooperation between different art forms in future issues.