When I’m with you I forget all my unhappiness. When I’m there I’m thinking only of you. What good times you have already given me – what great enjoyment you have bestowed on me! Most people, and especially those egotistical bourgeois men, don’t approve of your behaviour. It’s not appropriate for girls to engage with higher culture – well, they don’t understand it, it’s too elevated for ‘girls’. It’s not ladylike to go to meetings on your own. Mum or Dad should go with you.

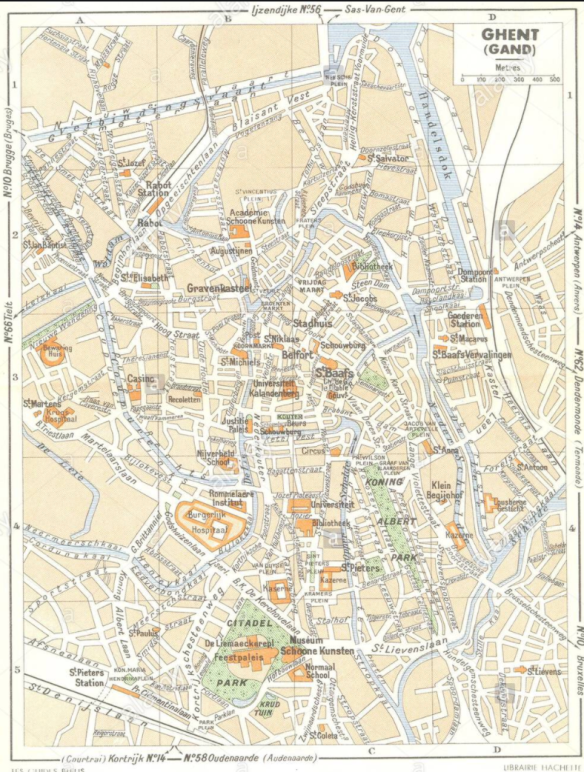

In this extract from her diary, written in November 1905, Alice Van Damme, the future wife of Gerard Ceunis, expresses her appreciation for her ‘club’, the Flinken [1]. May Sarton, whose mother Mabel Elwes was also a member, describes the Flinken as ‘a group of working girls from a…modest social background, girls who did not attend the university, but instead the École Professionelle of the city of Ghent, a business school that trained them to be secretaries and clerks.’ [2] Sarton explains that the group’s name is ‘an untranslatable Flemish word meaning ‘merry’ or in French, ‘gaillard’ (though the historian Denise De Weerdt translates it as ‘Les Courageuses’ or ‘Women with Spirit’):

Their language was primarily Flemish: their parents were small tradesmen, butchers, grocers: but just like the university students, the children of the ‘petite bourgeoisie’ were in revolt against their background, were fervently committed to plain living and high thinking, though their seriousness was tempered by a good deal of laughter and self-mockery. They were ardent feminists of course, called each other by surname, and believed that wives should support themselves.

It was through a member who already had a job that ‘two young women of the bourgeoisie’ joined the group. Marthe Patyn worked as a secretary for the firm of Dangotte, who were interior decorators, and she recruited Céline Dangotte, who had just joined the family business, and Mabel Elwes, a young English artist who was living with the Dangottes. The table below, reproduced by Christophe Verbruggen from a publication by Anne Marie van der Meersch, provides a useful list of the membership of the Flinken, together with their dates of birth, fathers’ occupations, their own occupations, and an indication of their higher education, where relevant [3]:

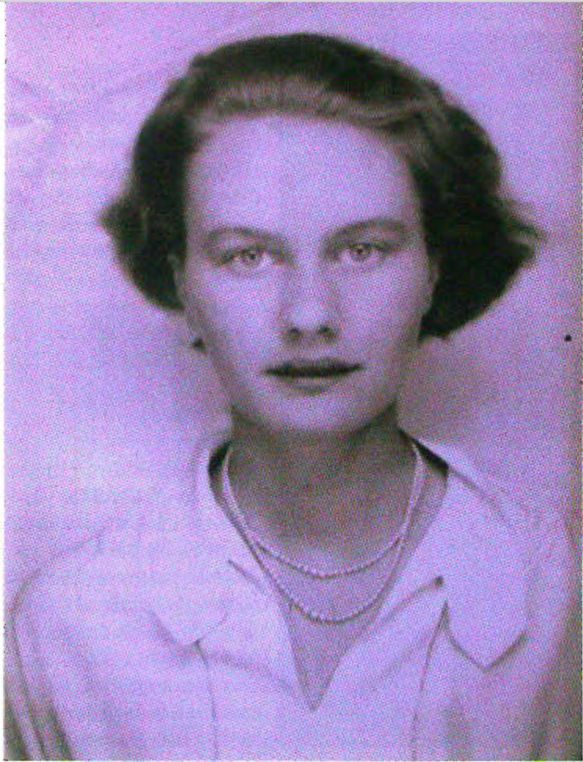

From this, we learn that Alice Van Damme, who would have been nineteen years old when she wrote the diary entry quoted above, was the daughter of a tailor (kleermaker) and that in 1910 she herself was working as a bediende, which I understand could mean either a clerk or a domestic servant.

Verbruggen’s chapter also reproduces this photograph of the members of the Flinken in 1906 or 1907, from Lewis Pyenson’s biography of George Sarton [4], but frustratingly it is unlabelled, which makes identifying Alice, or indeed any of the members, rather difficult (though I wonder if Céline Dangotte is the young woman seated third from the right, with Mabel Elwes standing behind her and to the right?):

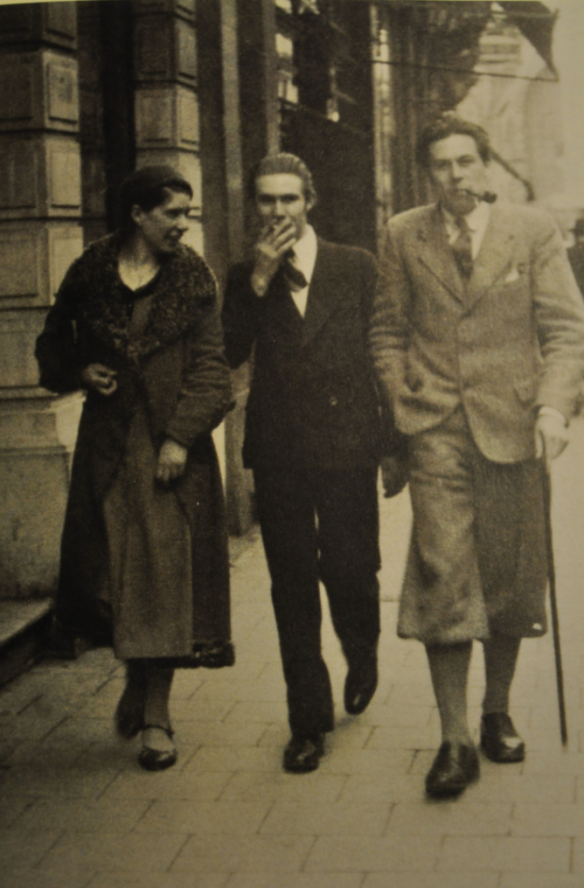

As May Sarton explains, it was through her membership of the Flinken that her mother, Mabel Elwes, first met her father, the future historian of science, George Sarton, when the group of young women came into contact with Reiner Leven (‘Purer Living’) the association of Ghent university students that George had formed with his friends, medical student Irénée Van der Ghinst and the future poet and philosopher Raymond Limbosch. The purpose of the organisation, according to May Sarton, ‘was to lift the brutalising level of student life and provide a centre for those who did not look to prostitution and liquor as major outlets for their energies.’ The group ‘arranged lectures on history, politics, art, vegetarianism, went on excursions and picnics in the surrounding countryside, or carried on discussions in their ‘local’ which was, significantly enough, the Temperance Café.’

Flinken / Reiner Leven excursion in Knokke, c. 1907-1908. Raymond Limbosch is front and centre, with his future wife Céline Dangotte behind him (AMVC-Letterenhuis, Antwerp, via)

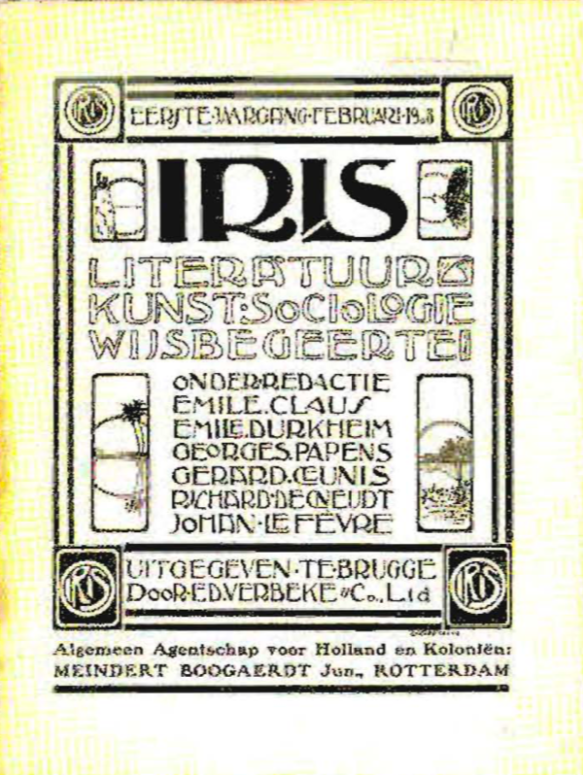

The association brought together young men with a variety of intellectual interests. According to Christophe Verbruggen: ‘Reiner Leven exemplified the synergy between visual artists, writers, scientists and other intellectuals during the Belle Époque.’ Besides Sarton and Limbosch, its members included the writers Paul-Gustave van Hecke and Paul Kenis, scientists Paul van Oye and Leo Michel Thierry – and of course Gerard Ceunis who, in Verbruggen’s words ‘joined the Reiner Leven association in the hope of finding kindred spirits there’. May Sarton tells the story of how the two groups came together:

The Reiner Leven young men were unaware of the existence of a sister organisation until they put an ad in the paper, for the purpose of recruiting new members at the university. The Flinken saw the ad, signed Irenée van Ghinst, and supposed that Irenée (spelled rather eccentrically with two final ‘e’s,) must be a woman. The Flinken despatched a pretty young woman called Mélanie Lorien to go and have a talk with Van der Ghinst. She was delighted, of course, to find that ‘the young woman’ was actually a charming, fanciful young man. Van der Ghinst reported the affair to Sarton and they agreed that nothing could be more appropriate than to include a group of working girls in Reiner Leven. It was a fairly daring departure from the social mores of the period and no doubt this fact added a certain pleasure to the whole affair. They went on regular Sunday expeditions together, walking through the country with their knapsacks on their shoulders, singing the Internationale.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a number of the young men of Reiner Leven ended up marrying members of the Flinken. George Sarton, after a brief romance with Mélanie Lorien, married Mabel Elwes. Raymond Limbosch married Céline Dangotte. Leo Michel Thierry married Augusta de Taeye. And, of course, Gerard Ceunis married Alice Van Damme. May Sarton quotes a letter from Raymond Limbosch to Mabel Elwes, who was staying with her family in England, bringing her up to date with all the news about Flinken friends, including a report on a conversation over supper ‘where we talked only of conduct between young men and women, with wit, good sense, revolt smallness, and meanness, quite a jumble! All this about Alice who was seen with a young man…but Céline will tell you all about that in detail.’

As there was only one Alice in the Flinken, it must be Alice Van Damme who is being referred to here. But it’s unclear whether the ‘young man’ in question is Gerard Ceunis, or his friend, and rival for Alice’s affections, Paul-Gustave van Hecke.

Christophe Verbruggen claims that Ceunis’ views on women were not quite as progressive as those of his fellow members of Reiner Leven:

Pretty soon Ceunis distanced himself from Reiner Leven and ‘De Flinken’, a group of feminists who had joined that society. He placed his fiancée Alice Van Damme in a difficult position, because she was a member of both clubs. Young women, in Ceunis’ opinion, should not be concerned with reading Maeterlinck or with vegetarianism. He was dubbed an anti-feminist, a reputation he himself nurtured with his misogynistic public statements. It earned him the scorn of half of Ghent.

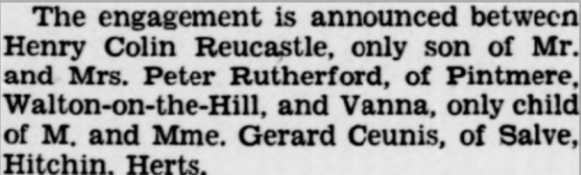

Nevertheless, the couple would eventually marry, have a child (Vanna) together, and emigrate to England following the German invasion of Belgium in 1914. And despite Gerard’s apparent anti-feminism, the couple maintained contact with at least some of their friends from Reiner Leven and the Flinken, particularly with Leo Michel Thierry and August de Taeye, whose son Herman, a.k.a the author Johan Daisne, would often stay with the Ceunis family in Hitchin, and after Gerard’s death in 1964, would do his utmost to ensure that the latter was remembered in his home country.

Notes

1. Diary of Alice Van Damme, 1905 (Cathcart collection), quoted in Christophe Verbruggen (2008) ‘”Vrouwelijke” intellectuelen en het Belgische feminisme in de belle époque’. In: Verslagen van het Centrum voor Genderstudies – UGent, (2008)17, p. 7-25. [my translation]

2. May Sarton (1959), I Knew a Phoenix: Sketches for an Autobiography, New York: Norton

3. Anne Marie Simon-van der Meersch (1982) De eerste generaties meisjesstudenten aan de Rijksuniversiteit te Gent, Gent: RUG Archief, reproduced in Verbruggen (2008) – see above [1]

4. Lewis Pyenson (2008) The Passion of George Sarton: A Modern Marriage and its Discipline, Philadelphia: Amer Philosophical Society